The battle for Total Basketball, vol. 1: Iowa State's ban on post-ups

Plus: the tactical handshake between TJ Otzelberger and Real Sociedad

In thinking about the upcoming basketball season, I’ve been gravitating a lot towards the Big 12. Not because I think it’s guaranteed to be the best conference or possibly even the second-best, as the Akira-like SEC and Big Ten will have more to say than usual about that. It’s more because I think it retains two very specific things about it that fascinate me:

The most recent consensus top 25 (taken post-Draft declarations, with most rosters fully settled) has four Big 12 teams among the top seven nationally;

Even with realignment wreaking some amount of havoc, the Big 12 has the most aggressive defensive personality of the five major conferences.

The second point requires some explanation. Last year’s Big 12, with 12 of the current 14 teams in its borders, had the highest steal percentage, highest assist percentage (implying teams are struggling to score 1-on-1), second-highest Havoc rate (steals + blocks) behind the SEC, and best defensive rating per 100 possessions in the entire nation. Their teams forced the lowest opponent 2PT% and the second-lowest 3PT%. In the three true post-COVID seasons, the Big 12 has cleared its closest defensive competition (the SEC) by nearly three points per 100 possessions, forcing more turnovers than anyone but the MEAC. I’m going to take a guess and say that given the talent levels of the two conferences, Big 12 perimeter defenses forcing that many turnovers is more impressive.

It’s not just the stats, though. A significant part of this is vibes that can be backed up with stats and video. This is a three-part series exploring two specific teams in the Big 12: Iowa State and Houston. Iowa State has the third-best defensive rating in all of college basketball over the last three seasons; Houston is #1. (Tennessee comes between the two, and I considered writing about them, but considering there is a now seven-year backlog of Tennessee articles, you can hunt through those instead.) Among 80 teams classified as high-majors from 2021 to now, Iowa State (#1) and Houston (#2) force more turnovers than anyone else.

It goes even further. Against Quadrant 1 competition, they rank fourth (Cyclones) and sixth (Cougars) in total wins since 2021. Along with Tennessee, these are the only two defenses to finish in KenPom’s top 10 of Adjusted Defensive Efficiency three straight seasons. In 2023-24, no team gave up fewer attempts at the rim than Iowa State…while no team allowed fewer made twos than Houston.

I thought about these two a lot over the last couple of months, particularly as I got to engage more in my other favorite sport, soccer. For two theoretically very different sports, the importance of tactics and defensive strategy - not to mention the importance of retaining possession - link up remarkably well. It got to the point that I couldn’t watch clips of these teams without thinking of their European offshoots they’ve likely never thought about once. Such is the life of a uniquely poisoned brain.

So, yes, this is a three-part series about Iowa State and Houston and somewhat about the surrounding 14 Big 12 teams that have to figure out how to crack them. It’s also at least a little about soccer, mainly how two things that look very different on paper have more similarities than you may expect. The goal for these first two parts is to explore three questions, plus a bonus fourth that could be good or truly terrible:

Why is this defense so good?

What Big 12 opponents has this system been best against?

What, if any, Big 12 (or other) offenses have found ways to crack the code?

Based on stats, video, and vibes, who’s their soccer comparison?

Part 1: Iowa State’s tactical handshake with Real Sociedad is below. Part 2 on Houston and Part 3 (Iowa State versus Houston versus the Big 12 Universe) will come out on August 19 and 23, respectively. These are FREE FREE FREE since this is the offseason, but subscribe below if you’re a new(er) reader.

What makes Iowa State’s defense so good?

At times in the past I’ve heard what I guess is an old adage of coaches everywhere: the best man-to-man defenses can look like zones, and the best zone defenses can look like man-to-man. I’ve heard this about a variety of schools in the last few years, notably Tennessee and Houston, but Iowa State certainly belongs on the list. What they run is nothing necessarily new but perhaps more a variation on an old tune: the no-middle defense. This first became prominent in the late 2010s with Chris Beard and Mark Adams’ Texas Tech teams, then became a championship staple with Scott Drew at Baylor at the start of the decade. Jordan Sperber’s excellent 15-minute video on that is a must-watch.

Iowa State runs a version of this that turns up the on-ball pressure and willingly sacrifices fouls for turnovers. (The last two ISU teams averaged turnovers on 25.2% on opponent possessions; peak Beard TTU averaged 22.9% and peak Baylor 23.3%.) More so, it’s uniquely tough to beat because no-middle really means no-middle here. For two straight seasons, these Cyclones have given up the fewest attempts at the rim of any team in America. While the peak Baylor and Texas Tech teams were very good in their own right at preventing rim attempts, neither ever managed a national finish higher than fifth.

So: how do you do that? Talent and athleticism matter, but that alone can’t get you to #1 in fewest rim attempts allowed. The basic principle of no-middle is what it says on the tin: no one is allowed to the middle third of the court. Where that starts, as it did with Baylor and Texas Tech, is the positioning of the player’s feet. Look at this screenshot from Iowa State’s 2024 Sweet 16 battle with Illinois.

Or this one, from a Big 12 Tournament game against Baylor.

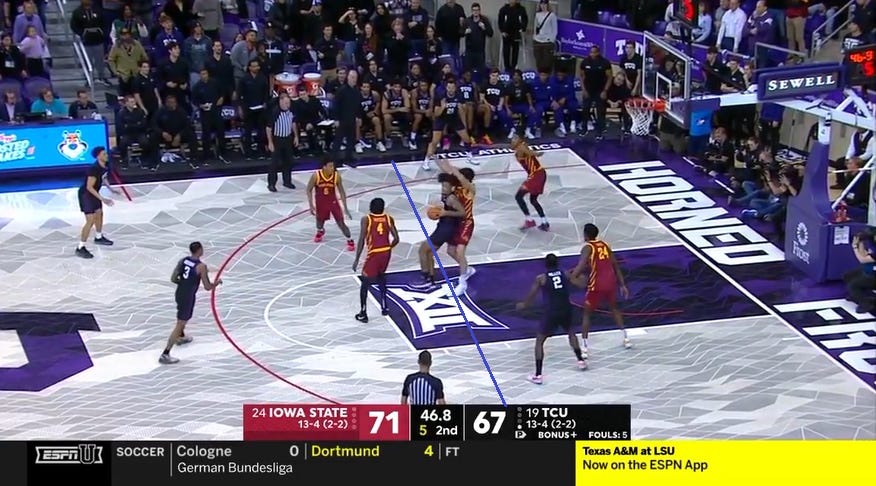

The on-ball defender’s feet are always pointed towards the nearest baseline when engaged. In both of these plays, neither team ever gets a single paint touch with a ball-handler and goes on to commit a turnover. That’s not the sole part of it, however. I think of it like a high-line pressure point, or alternately, where the top and median points of defender positioning is in a given possession. Take that screenshot above; the red line is the high point, the blue line the median line of pressure.

Or here, in another screenshot from their March battle with Illinois.

A lot of that is very opponent-dependent, but these are unusually high lines for almost any defense to be taking in a half-court set. Even in this one, against a TCU team that is pretty anti-shooting in general year-over-year, this late-game possession where TCU basically had to get at least a bucket somewhere from someone features a median line well above the restricted arc.

The best counter-example here - a high-end defense that has lower-end pressure but somewhat similar results - is something like North Carolina, who runs a version of the Virginia packline defense that focuses on closing gaps. It results in relatively few turnovers (314th this past season in defensive TO%), but a lot of one-on-one basketball and a similarly low number of attempts at the rim. Whereas Iowa State (and Houston) are aggressive to an extreme against pick-and-roll sets, North Carolina packs it in, stays low, and forces a tremendous number of pull-up jumpers. It’s an analytically smart play in its own right.

That type of setup looks more like this:

Look at how remarkably tight and packed-in this is. Four of North Carolina’s five on-court defenders are at or below the free throw line, with all within no more than two steps of the paint. Every defender is within the three-point line. The level of spacing allowed here is remarkably small, which is likely why UNC ranked 7th nationally in rim-and-three rate allowed and among the top in spacing allowed in general.

Iowa State is willing to let you have the threes, just not the shots down low. It’s like a reverse packline in a way, or perhaps a half-court press. Here’s a possession from their late-season win over BYU at home. As a reminder, this year’s BYU team was a top-15 offense that shot 58% from two and dropped 1.2 PPP or better on all of Texas, Baylor, NC State, TCU, and yes, Iowa State. (We’ll get to that one.) After a horrid offensive half from Iowa State and a fairly rough one on defense, this is the first possession of the second half.

Here are three immediate things I notice that you should notice too.

The ball never touches the paint in this 30-second possession from one of the best offenses in basketball.

The one post action is immediately doubled.

Iowa State is willing to let BYU take a three here.

The second note gets covered in the next section, and the first is no surprise given the point of the no-middle defense. But uniquely among this style of defense, Iowa State is perfectly happy to give up three-point attempts all day long. From time to time, it gets them burned against hot opponents, and they’re the first elite defense I can recall covering in recent history that actually allows more open catch-and-shoot threes than guarded ones, per Synergy. To Otzelberger and crew, this is all worth it in the name of avoiding attempts at the rim.

These are two shot charts from CBB Analytics. The first is this, which shows the relative frequency of shot attempts from each area of the court for the entire season for ISU’s defense.

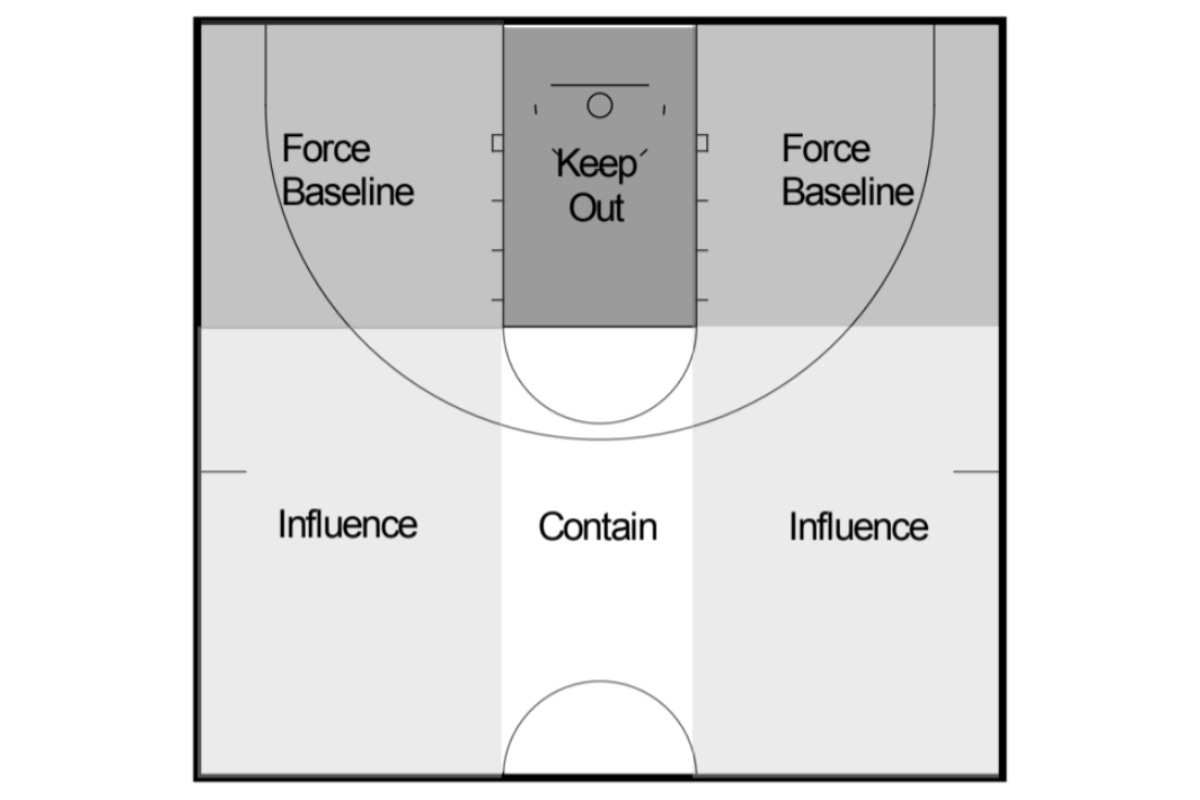

That can tell you one extremely obvious story about this defense. Iowa State forces everything to the boundary, including the corner threes teams supposedly want to take but also a significant amount of baseline jumpers. Even the wing threes, which aren’t that high relative to the national numbers, still happen with fair frequency. If you take the no-middle defense’s most explanatory chart at face value it’s showing the Cyclones performing it to perfection.

The other shot chart is this one. It’s the same as before, but in the final 10 seconds of the shot clock. When Iowa State says “keep out,” they mean it.

It’s one thing to contain and influence; it’s another to force, particularly in those first 20 seconds of a half-court set. The no-middle alone can’t fully solve that, but hyper-aggression in one key area sure can.

TJ Otzelberger’s personal vendetta against post-ups

In the COVID year of 2020-21, TJ Otzelberger was the head coach at UNLV. This lasted all of two seasons, coming off of a fairly successful stint at South Dakota State. Frankly, not much of the UNLV stint was that memorable. A pandemic-influenced pair of seasons resulted in a 56% win rate in MWC play and a 29-30 record overall. In his first five seasons as a head coach, Otzelberger produced four top-75 offenses at places that don’t usually see that level of offensive success. He oversaw zero top-100 defenses in the same span of time.

Otzelberger’s final game at UNLV was an unremarkable conference tournament quarterfinal blowout against a pretty good Utah State team. That USU team had a very good post player named Neemias Queta, a guy in the midst of a February/March heater who proceeded to drag UNLV to hell. Utah State dropped 18 points on UNLV from post-ups alone en route to a 74-53 demolition, 13 of which came in single coverage. This was pretty typical for the season, one in which UNLV allowed more post-up possessions than 91% of the Division I participants.

Apparently, this unnerved Otzelberger so much that he resolved to never allow a single post-up point ever again in his career. Iowa State has now played 105 games with Otz as their head coach. The peak number of points scored from single-coverage post-ups, in any Iowa State game, is eight. Teams have gotten to six or more all of three times, which is lower than UNLV’s 2020-21 per-game average. In three straight seasons, Iowa State has ranked either first, second, or third in number of post-up attempts allowed per game. The others with them are generally zone defenses or teams that employed Zach Edey.

Considering that most post-up field goal attempts are going to end with a shot within five feet of the rim, this part of the Iowa State philosophy makes sense. More so than quality on-ball defense is the denial of post positioning even happening to begin with. In a February newsletter, Jordan Sperber touched on this:

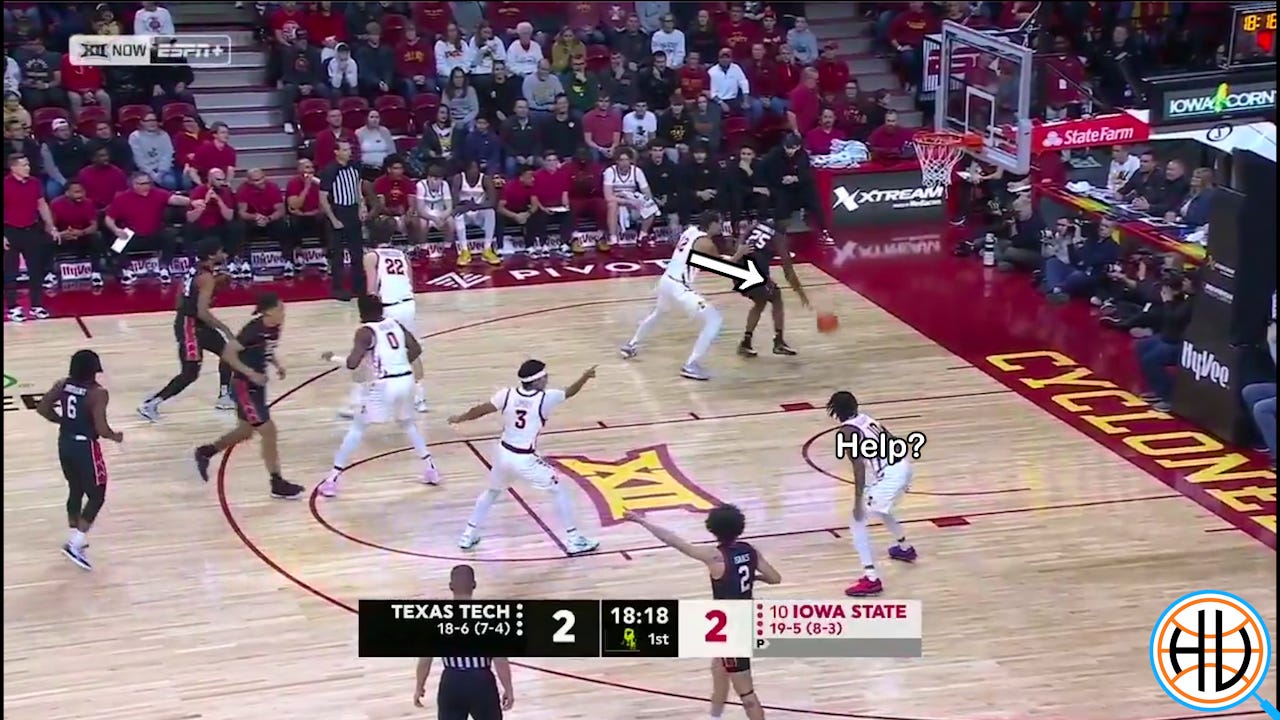

Iowa State forces the ball to the baseline when it goes into the post (no-middle) and brings help with the lowest defender.

Here’s an example from Iowa State’s game on Saturday against Texas Tech where #12 Robert Jones is aggressively sending the ball baseline.

This is a rare instance where Iowa State’s help defense is late. You can see that #3 Tamin Lipsey is looking at #10 Keshon Gilbert and pointing — indicating that Gilbert needs to get in help position by moving towards the ball.

Because Jones is so aggressive in pushing the ball handler baseline, that low man defender must be there early in order to prevent a potential easy basket.

Here’s an example of post denial to begin with. This past season, Kansas used post play more than anyone else in the Big 12, which is unsurprising considering their system is centered around large man Hunter Dickinson. Kansas averaged 11.5 points per game on post-ups, including passouts, this past season. Against Iowa State, they scored five and had four fewer possessions in the post than an average game. Instead, it resulted in Kansas taking 27 jumpers, which was tied for their third-highest rate of the season. Despite taking care of the ball well and out-rebounding ISU, Kansas still lost in part because of an inability to generate the quality twos their offense needed to sustain itself.

This possession saw Dickinson attempt a hard post move that would’ve needed a hard over-the-top pass; instead, it was a P&R Iowa State blitzed that turned into a corner three for a 34% three-point shooter. Dickinson post-ups resulted in 1.21 points per shot this season, while that three works out to 1.02 points per shot.

Here’s an example of the post double Sperber talks about, the very first possession of this game. Dickinson was doubled somewhat frequently this year. He’s a pretty solid post passer, so he’s able to get out of this, but against Dickinson and every other quality post player they’ve faced the last three seasons, there’s an outright refusal to let anything come easy. The speed at which Milan Momcilovic spots this is remarkable; Dickinson must either attempt a wild pass, burn a timeout, or bully his way through it. Few even attempted the latter, though Dickinson’s skill is such that he can give it a real go.

Similar to Sperber’s terrific P&R Aggressiveness Index (which Iowa State ranked 21st most-aggressive in), I used a similar function to find out which teams were the most aggressive in both post-up denial and doubling the post once the ball got there. Iowa State was #1 by a mile in the first metric and #3 behind McNeese State and Mississippi State in the second. Between them and Houston, you’re looking at what I’d call the two most aggressive half-court defenses in the nation.

So: how do you beat it?

Prayer is a good start, but it’s the same way you beat any version of the no-middle: the skip pass. Dickinson actually managed it within this same game, passing out of a double to a wide-open Johnny Furphy for three. Not everyone is this patient with the ball, but it goes to show: you can beat it.

Not many have, but the one Big 12 team with their coach returning for 2024-25 that has is Baylor. No team has posted 1+ PPP against Iowa State in more games (four) than the Bears, and only Kansas State has committed fewer turnovers against Iowa State on average over the last three years.

What’s Baylor’s secret sauce? Well, perhaps it’s an obvious one: they already know how to beat it because they’ve practiced against it as a program many, many days in the last decade. Even during the four years in which peak Baylor and peak Texas Tech crossed over, Baylor went 6-2. Even in a Big 12 Tournament win in which ISU held Baylor to 0.924 PPP, it was mostly because Baylor had their third-worst 3PT% of the season. (They went 4-for-14 on open threes, per Synergy, after making 47% of them during the season.) They even have a shot chart that plays into what Iowa State allows, at least in the final 15 seconds of the shot clock.

Against Iowa State, Baylor’s guards were pretty good at finding these skip passes, and in general the Drew system has been great at ball movement/hunting open shots for essentially 15 years now. Iowa State’s general bet is that most teams aren’t going to be able to move the ball that well to catch how many 4-on-3 situations this defense is capable of giving up. Of course, most teams aren’t Baylor, or perhaps Illinois. (If only they’d had the chance to play Alabama or UConn.)

Other than that, the most proven way to score points on the last three Iowa State defenses has been generating offensive rebounds. The Cyclones do a lot well but they’ve been pretty middling at protecting the boards, which is perhaps not that surprising when you see how far they extend themselves across the court. Four of ISU’s 2023-24 losses saw them give up a 36% OREB% or worse, and six of the eight teams that bested them ranked in the top 75 nationally in OREB%.

This year’s team, with a presumed starting frontcourt of two 6’8” guys, is probably no different. In general, this is a small(er) team that gives up a ton of three-point attempts and a healthy amount of second chances, so on occasion (87-72 loss to BYU in January 2024, 78-61 to Mizzou in January 2023) they run into a team that goes bonkers from three and defeats the purpose of the system. However, those games stand out so severely because of the system itself. It simply doesn’t allow many games like it.

4,400 miles away, their counterparts

The Basque Country on the northern coast in Spain and Ames, Iowa presumably have very little in common, though Iowa State does have waterfront property in the form of a campus lake.

What they do have in common is one very specific thing: a local team that plays an aggressive, hard press that forces a lot of turnovers and generates results well above their means. Located in Donostia-San Sebastian, Real Sociedad play a very regionally-appropriate brand of football aimed at punching above their weight. Along with Basque counterparts Athletic Bilbao (who still don’t allow any non-Basque player on their roster), Sociedad aim to have no less than 60% of their roster built from their own region, along with 80% for their academy.

Iowa State isn’t limited to that extent, but consider the fact that Otzelberger has seen just three top 100 recruits walk through the doors in his three seasons, two of which aren’t on the roster anymore. The average Kansas roster in a given year this decade has had six per season. Iowa State’s had a total of five top 100 recruits at all since 2011. Like it or not, it’s not the most popular place in the world to go if you’re a young athlete looking to strike it big, especially with a system that prioritizes defense above all. Iowa State’s 2023-24 roster had all but three of its 15 players from within a 300-mile radius of their campus.

As such, the talent pool is relatively limited. Using Bart Torvik’s Talent Rating, which is based on a combination of recruiting ranking and on-court production, Iowa State had the 63rd-most talented roster in college basketball last season. Otzelberger and crew turned that into a 3 seed that won 29 games. The year before that: 88th in talent, 29th-place finish.

Their Spanish counterparts have experienced similar overachievement. Armed with somewhere between the 7th and 10th-highest operating payroll in any given La Liga season, Real Sociedad have managed five straight top-six finishes in La Liga, including a fourth-place finish in 2023 that resulted in just their second Champions League bid in twenty years. Under manager Imanol Alguacil, they’ve installed a style of play that results in very few comfortable possessions for the opponent. For four straight seasons, they’ve ranked in La Liga’s top four in goals allowed.

The most direct comparison I can make is predictably a statistical one. There’s this stat called PPDA, which is Passes Per Defensive Action. Functionally, it’s a measure of how high a team’s press is. The lower the number, the more regularly you’re interfering with the opponent’s run of play. Among a loaded list of options for the 2023-24 season in Europe’s top five leagues, it was Sociedad who led the pack at 7.56 PPDA.

This was actually a step back from their 2022-23 form that earned Champions League entry at 7.29, which is the lowest any Top 5 team has recorded since 2020-21 Leeds United (7.17). You can watch this for an example of a physical, aggressive press that results in a goal from Sociedad’s top player, Take Kubo.

Or this, in which Inter Milan - one of the five best teams in all of Europe last year - are turned into silly putty by the extreme aggressiveness of this system.

There’s also the bit about how they allowed fewer touches in the 18-yard box (the bigger box you see near the goal) than all but five teams in Europe last year. Considering the teams ahead of them were groups like Arsenal, Manchester City, and Bayer Leverkusen (who went undefeated in Germany’s Bundesliga), you can say they protect the proverbial rim as well as anybody. Only Leverkusen gave up fewer carries into the box.

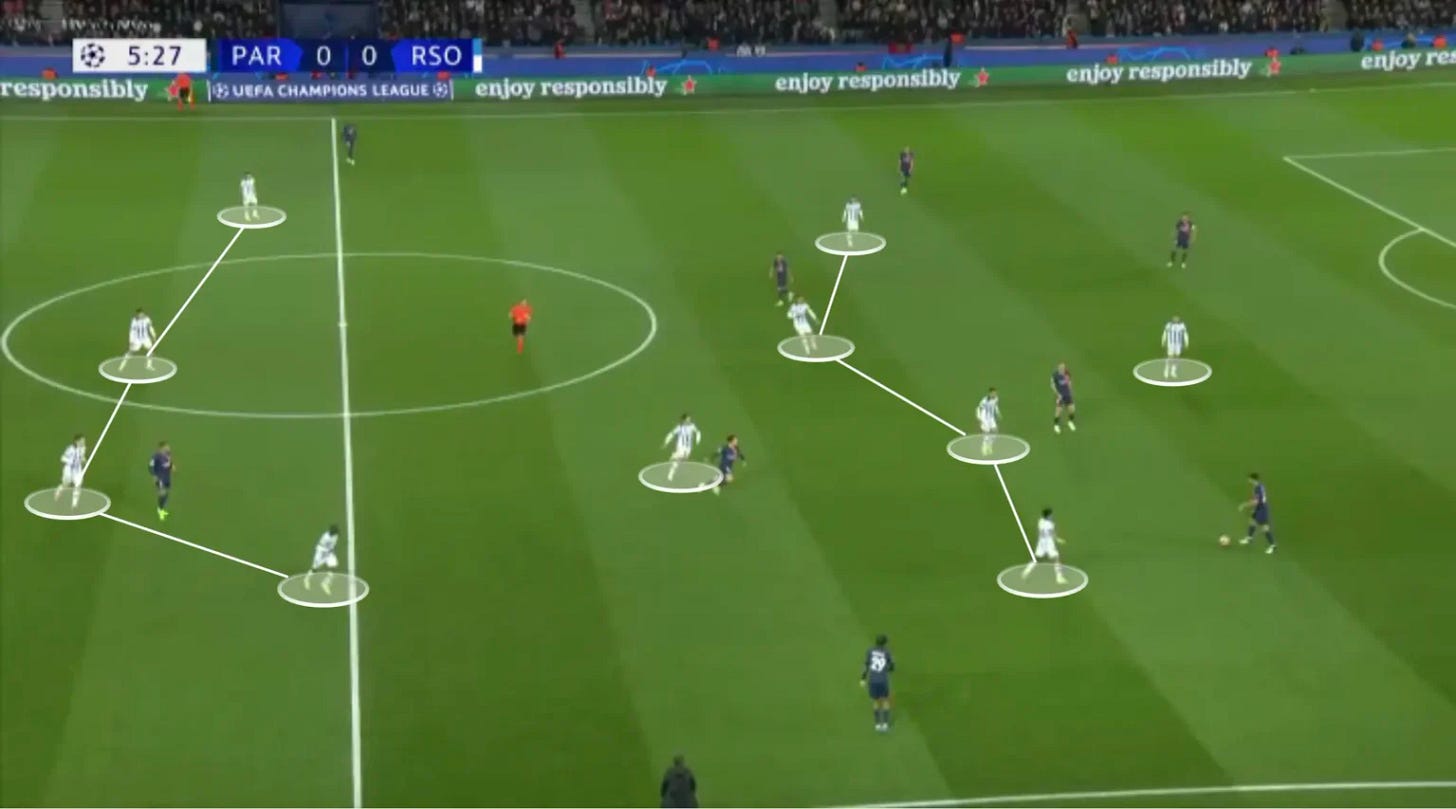

The setup here looks like this, tactically. Real Sociedad run out various different formations (I’ve seen them line up in a 4-1-2-3, a 4-2-3-1, a 4-1-3-2, a 5-3-2, a 4-3-3, and even the odd 5-2-2-1) the general thesis of what they do remains the same. How they create offensively is interesting, but not the point of why we’re here. It’s how they operate out of possession that I adore. You can see here, against Paris Saint Germain, just how high their press operates:

Or here, which shows a similar commitment to a high press and a total lack of space for the powerful PSG to operate. PSG (a far, far richer and more talented club) would go on to win 2-0, but it took them almost 60 minutes to finally assert their dominance in some fashion.

Similarly to a team like Liverpool, you’ll notice while watching that Sociedad focus less on man-to-man defense and more on little zones that their players operate in. Think of it like soccer’s version of a matchup zone: a zone so amoeba-like that it looks like man-to-man, or a man defense so amoeba-like it looks like a zone. Add in the fact Real Sociedad managed just two (2) goals off of 49 dangerous turnovers forced last year, per Opta, and you really do have the perfect Iowa State comparison: a team that simply refuses to let much scoring happen anywhere.

The beauty and stupidity of a piece like this is that it’s probably not all the way accurate. Smarter people than I who watch more soccer than I’m able to might be able to make a better 1:1 comparison. The point of this is less about accuracy and more about August. This is the offseason. If there’s any time to take a deep dive on two similar-yet-different defensive approaches in college basketball and the potential tactical throughline to a different sport, it’s probably right now. Beats a piece on the top ten transfers or whatever.

Anyway! If you’re a resident of Ames, Iowa and you’re even somewhat intrigued by the idea of kicking a ball with your feet, you might want to invest in an ESPN+ subscription this year. After all, the day before an early season tune-up against UMKC, you can watch Real Sociedad take on Barcelona on a Sunday morning. You may discover you’re more alike than different.

Great article! Mikel Arteta has said that he gets a a lot of inspiration for tactics from basketball. The fast break parallels are obvious, and I think the "rebound rule" that they talk about in here is interesting as well

https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/5572113/2024/06/20/have-other-sports-influenced-arsenals-rise-rebounds-rotations-and-a-pendulum-defence/

Finally got around to reading this today and boy was it worth the wait. Awesome stuff, Will.