On January 11, 2025, Utah (8-6, 0-3 Big 12) played Oklahoma State (9-5, 1-2 Big 12) at 7 PM Eastern on ESPN+. This was notable to no one except fans of the two teams or perhaps Big 12 obsessives. Per KenPom’s FanMatch score, it was the 32nd-biggest game of that Saturday, one spot behind a Northern Iowa/Illinois State game.

On January 25, 2025, two weeks later, Utah (11-7, 3-4 Big 12) played Baylor (12-6, 4-3 Big 12) on a Saturday at 4:30 PM ET on ESPN2. This game was the seventh-best game of its day, per FanMatch, but consider that its contemporaries this day were an Oklahoma/Arkansas game I’m not sure anyone recalls, alongside a similarly-rated Iowa State/Arizona State game you definitely don’t remember.

Frankly, neither of these games, on face value, are worth remembering. In fact, Utah - the protagonist of our story today - didn’t even win both games. They defeated Oklahoma State 83-62; they lost to Baylor, 76-61. In one game, against the 72nd-best defense in America, they scored 1.19 points per possession. Against the other, the 62nd-best defensive offering, just 0.98. Still, swings in games happen.

Except there is something odd going on here, which I began noticing in January and felt even more upon postseason review. The headline is that Utah rated out with elite company in one specific manner.

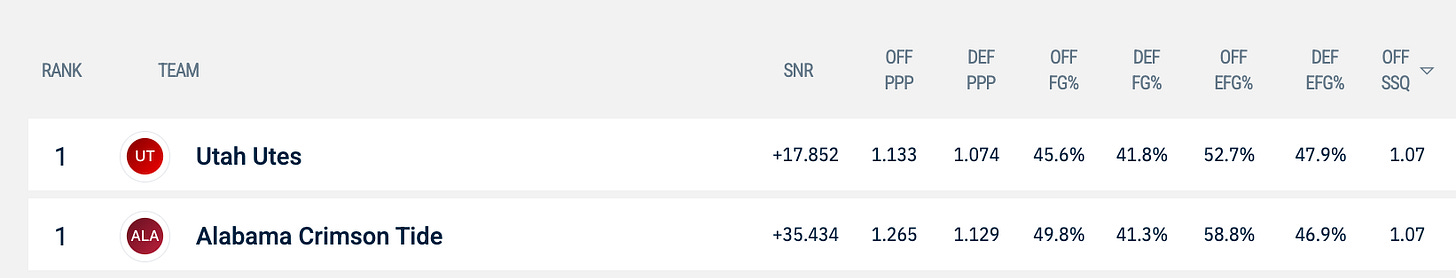

Adjusted for competition, the two highest shot qualities produced on offense this year were Alabama and Utah. This doesn’t take into account anything involving the players on the court, their ability to hit these shots, or the talents at play. It is strictly “was this a good shot” for an average basketball player on an average basketball team. From the time I picked up on this in January to the day I’m writing this, Utah was inside the top 3 or #1 overall in offensive Synergy Shot Quality.

Whereas services like Shot Quality adjust for players’ history, the system’s history itself, and more, Synergy strictly looks at the average production of said shot from the location of the shot itself. Attempt a layup? That’s an expected 55% hit rate, or 1.1 points per shot. Pull-up midrange two? 37.5% hit rate, or 0.75 points per shot. You get the gist. At 1.07 expected points per shot, the Utes registered the 10th season of 1.06 expected PPS or better (adjusted for schedule) over the last five full years (excluding 2020-21).

Perhaps stranger is that, defensively, they ranked top-25. In terms of pure systems, Utah ranked alongside Alabama and Creighton in producing the best two-way shot quality at an average of +11 points per 100 possessions. Unlike Alabama (-1.22 SVI) and Creighton (-7.59), they did not possess a significant shot volume disadvantage, actually generating slightly more (+0.2) shots than their opponents. Unlike Alabama (2 seed, Elite Eight) and Creighton (9 seed, Round of 32), Utah did not make the NCAA Tournament. They didn’t come close.

Was it our old favorite, three-point variance, that got Utah and led to Craig Smith’s firing on February 24? Not really; they shot 33.2% to opponents’ 33.7%. Louisville had similar splits and got an 8 seed. Poor 2PT% offense or defense? Nope. The Utes were +8.4% from two pre-firing, in line with 7-seed Kansas (+8.6%) or 4-seed Arizona (+8.1%). They had a solid rebounding margin, got a lot of free throw attempts, played a mathball-friendly style, and even their negative turnover margin (-1.7 per 100) wouldn’t have been a disqualifier for March. Ask Illinois (6 seed, -2.6) or Alabama (2 seed, -3.4).

It was none of these things. It was an objectively good system with objectively good top-line numbers in most areas, along with reasonable defensive metrics. And yet, at the time of Smith’s firing, it led to a 15-13 (7-10 Big 12) record that left Utah on the outside of the NCAA Tournament for the eighth straight year (fourth under Smith). Sometimes, our best-laid plans don’t go the way we hope for a variety of reasons. Unfortunately, our protagonist, Craig Smith, learned that the hard way. These two games, undistinguished to most, help tell the story.

The first game, played in beautiful Salt Lake City, had 7,922 people show up to the Jon M. Huntsman Center, or roughly about 53% of seats filled. The rare crowd shots you get during this game reinforces the vibe of “this is a basketball game, but not a particularly noteworthy one” quite well.

This game is one I picked because it’s pretty good at showing what Craig Smith was thinking when he built this team. Smith’s version of mathball is the same as a lot of coaches who want to play mathball: threes, layups, and dunks are the best shots you can buy. The starting backcourt of Gabe Madsen and Mike Sharavajamts combined to take 431 threes and Madsen alone made 101 (second-most in the Big 12); the starting frontcourt of Ezra Ausar and Lawson Lovering combined for 79 dunks (the third-highest combo of any Big 12 frontcourt, behind Cincinnati and Kansas) and 199 shots made at the rim.

While quite tall for college hoops - Utah’s average height of 6’7.5” was third-highest in the sport this year - what the Utes were doing was…well, fairly normal, at least at one level. The Utes’ most-used lineup went 6’4”/6’6”/6’8”/6’9”/7’1”, which earned them the rare feat of being one of two teams (Duke) to rank in the top 40 of positional size at all five spots on the floor this year. They also got to be part of an even rarer group: Power Five teams averaging 6’7” or taller in the KenPom era that ranked inside the top-100 in three-point attempt rate. (That’s a four-team list: Utah and Duke, plus 2018-19 Syracuse and 2014-15 Wisconsin.)

At a surface level, you could completely see the vision: a team that used its height to generate great looks at the rim, could run in transition, was able to use their height to get a lot of shots off, generated second chances, and could offer a ton of off-ball cuts. It’s a quality, modern concept that we’ve seen work elsewhere just fine. On this night in early January, it worked.

Prior to Smith’s firing, Utah ranked second-highest in the nation in High-Low usage behind Michigan, per Hoop-Explorer. Michigan offered a pair of seven-footers and the most unique (if not best) P&R attack in the Big Ten; Utah had Ezra Ausar and Lawson Lovering. With this frontcourt, across 697 possessions, Utah outscored opponents by a schedule-adjusted 23 points per 100 possessions, won 2PT% by 6.9%, smoked opponents in the rebounding and foul departments, and - you guessed it - won the rim battle pretty heavily.

It wasn’t just that Utah ran a ton of these. They were also really, really good actions, sitting in the 89th-percentile of offensive efficiency nationally. Ausar was Utah’s best player by some metrics and Lovering a starter-level piece; together, they were a pretty solid pairing. Here, Lovering stays on the perimeter (his 22% Assist% was exceptional for a big) and hammers Ausar inside. Of Lovering’s 76 assists this season, 21 were to fellow big Ausar, a nice 28% chunk. Again: pretty unusual when your average big sees most of his passouts go for threes.

Against defenses that over-rotate or help a bit too much defensively, this sort of high-low action can be unstoppable. Against Oklahoma State, I counted four straight possessions that ended in a high-low in some form before a Cowboys timeout to adjust. Big-to-big passing situations were a pretty ideal fit for a roster where four of the seven or so most impactful pieces were frontcourt players.

Along with that, Utah had a higher usage than most of flashing their bigs to the middle, continuing leaning on the high-low action to go to work. Both Lovering and Ausar set a screen for Madsen to come off of, but only one rolls to the basket. The other (Lovering) stays up and waits for Ausar to be switched onto a smaller defender. Using OKST’s deflection-heavy aggressiveness against them, this allows Ausar to turn this play into one quick post pin for an easy two.

It doesn’t really work if Madsen’s not as fearless as he tended to be, though. Madsen’s main headline is obviously as a shooter - 300+ three-point attempts in a year can do that - but no one on the roster attacked the rim more frequently or better than Madsen, whether in half-court or in transition. Because Madsen was so willing to shoot it, this generally led to him getting picked up further out from the rim than most. Utah ran a lot of off-ball actions for Madsen to get open for three, but because everyone did expect the three, he could take advantage of this to get downhill.

The Oklahoma State game was like a two-hour demonstration of the best simulation of Utah offensive basketball, more or less. Usually when we talk about teams and imply they were unlucky to did something wrong, we gravitate to “took too many threes” or “too much midrange” or “didn’t rebound well” or whatever. Utah did none of that on this January night: 22-33 at the rim, 12 (!) dunks, and a 6-15 effort from deep. They took a rare loss in the board battle, but when the opponent suffers seven blocked shots and you only have 28 attempts to get a shot back to begin with (Oklahoma State: 51!), it’s not that meaningful.

Pretty much everything worked the way it should. The Utes ran and ran fast, with backup big Keanu Dawes being the beneficiary of a five-dunk night.

Utah was so tall, so overpowering, so brutal to deal with in this game that they barely had to attempt jumpers at all. When they did, said 6-15 effort was pretty solid on a limited sample size. Former NBA Draft Twitter star Mike Sharavjamts continued what would be a six-game streak of making at least one three a night. When four different players make a three, four different players get at least one dunk, and only one of those (Madsen) is the same person, you’ve got quite the fun and shifty roster.

Utah’s fairly intoxicating mix of rim-and-three philosophy with excellent passing and overwhelming rebounding presence is…well, hard to find across history. Per Stathead, there’s just 77 teams over the last 30 years to post 11+ offensive rebounds a game, 17+ assists, and 26+ defensive rebounds while posting an eFG% of 51% or better. Across a 31-game slate like Utah had, these teams averaged a 24-7 record. After winning this game, Utah was 9-6. I imagine you’re aware they did not go 15-1 after.

Here is a full list of the aforementioned teams over the last five full seasons (COVID ‘20-21 excluded) that have posted a 1.06 or higher expected PPS value at Synergy. The ranking beside them is their KenPom adjusted offensive efficiency ranking for that year.

2019-20 Dayton: 2nd

2019-20 Kansas: 8th

2019-20 Stanford: 143rd

2021-22 Arizona: 7th

2023-24 UConn: 1st

2023-24 Alabama: 2nd

2023-24 Arizona: 11th

2023-24 Indiana State: 13th (7th unadjusted)

2024-25 Alabama: 4th

2024-25 Utah: 82nd

In general, having a system that generates really good shots typically leads to really good results. Six of these ten teams finished 8th or higher, and all but Utah and 2019-20 Stanford finished inside the top 13. That leaves two teams as monster outliers: a 2019-20 Stanford team that would’ve been squarely on the bubble had the Tournament happened, followed by a 2024-25 Utah team that didn’t come close.

Even then, 2019-20 Stanford was nothing like the Utes. That team actually did make a lot of shots. They finished 27th in eFG%, shot 37.3% from deep, and were fine from the line. The problem was getting off shots in the first place, finishing with the worst shot volume by any top 100 team in KenPom by several miles. (They ranked 11th-worst nationally; the next closest top 100 group, 93rd-worst.) Normalize Stanford’s shot volume a bit to that year’s average, even by five points per 100, and it’s a top-50 offense. Nothing amazing, but useful enough.

Utah was not that. As mentioned earlier, Utah was actually top-50 in OREB% and sat inside the top 100 for offensive shot volume this season. And, again, they ended the year +6.4% from two, +8.4% pre-Smith firing. Also! They were #1 in the nation in Assist Rate this year, generating 17.4 assists a night on 26.5 field goals per game. Do you want to know what happens to teams that do these things? Well, they usually win a ton of basketball games.

Usually.

Every team in the entire sport has bad nights. Everyone! Even Florida, this year’s champion, lost a game 64-44 to Tennessee. Houston, this year’s runner-up, lost three games in the first month of the season. Tennessee - my beloved freaks, Tennessee - lost a game by THIRTY POINTS. It happens. The problem is when one becomes two, two becomes three, and so on.

Anyway, did you know that Houston (three) and Utah (two) had nearly the same number of games with an eFG% of 60% or higher in conference play? I doubt it. Did you know that Utah had the second-most Big 12 games with an eFG% of 45% or lower, only trailing an abhorrent TCU offense? Well, perhaps. They did that seven times out of 20 chances, which…is not ideal.

This night against Baylor, two weeks after one of their best offensive efforts of the season, is one of the seven. Generally, when a team shoots like garbage, we spout out some variety of cliches: “not their night,” “didn’t try hard enough,” “didn’t want it enough,” “just gotta make shots,” whatever. All fine in a vacuum, I guess. All not terribly useful as in-game analysis. Also, none of them apply to this game in particular, because what Utah ran on this night was almost the exact same stuff they ran every night.

On this night, Utah put up five dunks, the third-most Baylor surrendered in a single game in 2024-25. Of Utah’s 57 field goal attempts, 29 were layups or dunks. Baylor had just seven players available for this game, and Utah did a tremendous job of leaning into their size/stamina advantage. Of the 63 possessions, 29 ended in a post-up, a big man cutting/rolling to the basket, or a transition attempt. I would argue that this is indeed good, particularly when their expected usage rate in a 63-possession game would be 24 possessions.

An additional 23 were threes. That’s a 52-for-57 (91.2%) mathball rate. Again: exceptional! We build statues of this if you do it in the NBA.

That’s before we get into the threes themselves. 15 of the 23 were true catch-and-shoots, seven of which were considered wide open by Synergy. Of the remaining eight dribble jumpers, I counted three as being wide open in my video review. While not perfect, a 44% rate of generating wide-open threes is pretty solid. (The national average is 43.9%, so a bang-average night of good looks.)

In all, when you look at Utah’s shooting splits from the season, you get the appeal pretty quickly.

99th-percentile in dunks and 76th-percentile in rim attempts.

75th-percentile in unguarded three-point attempts.

#1 in America in 80th-percentile or higher shot attempts at Synergy.

#1 in America in backdoor cuts usage, the play type with the highest expected points per shot at synergy.

In this game, it all came to fruition. The high mathball rate, a rim-based attack to take advantage of Baylor’s height and stamina issues, and excellent ball movement against a defense that allowed an unusually high assist rate…you can find it here. In theory.

Instead, this game was the reality, or at least a pretty low end of the simulation. Utah was a big, big team that could play fast or slow, could go inside or outside, could play high or low. In theory. The players picked to do all of these things had flaws, and some nights, they showed pretty severely. High-quality spacing that opened up driving lanes to the rim failed to punish the defense.

Exceptional possessions, with wide-open looks created by great actions and ball movement from the Utah offense, too frequently resulted in zero points.

In this game, Utah managed to turn those 10 wide-open looks into just three made shots, shooting 5-23 overall from deep. Frankly, that in itself is not impossible to survive, especially on a night where Baylor was just fine from three (9-24) and went a horrid 12-29 at the rim. In fact, situations like Utah’s happen pretty much every year: a team shoots poorly (<22%) from three, but still wins because of a high rebound rate (>35% OREB%) and shooting well enough on twos (>50%). It happened 112 times in 2024-25, and the team that did that went 62-50. You were actually more likely to win than lose even when you shot kind of poorly from deep, as long as you took care of the other stuff.

Further, holding Baylor below 50% as Utah did increases your odds that much further; teams that met all this criteria went 47-26 last year. It’s not perfect, but it’s a fine-enough formula for a one-off game. Of the 26 losses, the average margin of loss was five points, and just four of these cracked a double-digit margin. The peak margin of loss: 15 points. Which game? Well, you’re reading about it.

How does this happen? How can such great plans be sent wayward, particularly in a situation where Utah was actually more likely to do well than their opponent in an average simulation of this game? It’s a pretty simple additive effect, obviously; Baylor outscored Utah by 12 from three, while Utah only beat Baylor by two points from two. That’s a ten-point margin. Still, it wouldn’t explain it properly.

Utah and Baylor shot the same number of free throws (20). In that 73-game sample, the Utah-style teams averaged a 71.7% hit rate from free throw land; Baylor would’ve averaged 73.3%. That’s either a zero or one-point advantage, depending on your preference. Still, Utah losing a game like this by 10 or 11, while on the outlier end of outcomes, wouldn’t be the most extreme of the season.

Let’s cover a few offensive stats from the date that Craig Smith was fired one final time.

A 52.4% eFG% (96th-best).

34% OREB% (60th).

36.5% FT Rate (73rd).

First in Assist Rate.

54.8% from two (57th).

35th in rim-and-three rate.

Actually, you might want to know the defensive stats, too. Despite opponents shooting 41.3% on midrange jumpers, about 3-4% above expectation, Utah still had the 27th-best 2PT% allowed (46.4%). At that time, exactly five Big 12 teams (Utah included) sat at +7% or better on twos: Texas Tech, Iowa State, Arizona, and BYU. Three of those made the Sweet Sixteen or better, and the fourth was a 3 seed derailed by injuries.

But: I do have one final stat. It is as follows: at the time of Craig Smith’s firing, Utah was shooting 62.7% from the free throw line, which was good enough for 361st in the nation. Considering there are 364 teams in Division I basketball, this is far from ideal. It goes back to one major, possibly overlooked flaw with the roster construction itself.

Based on Utah’s 2024-25 personnel in the preseason, to-date career stats would’ve projected about a 34.3% hit rate from three for the Utes. On the year, they shot 32.7%, though prior to Smith’s firing this was 33.2%. That’s not that far off line; some amount of small variance is reasonable. Still, if you wish, you can say Utah got a little unlucky on threes this year, which is fine.

On free throws…well, there’s your problem. To-date career stats would’ve projected a 64.4% hit rate from the free throw line. Utah ended the season at 64.1%, the 357th-best offering in the sport. Considering they had acceptable-enough deep shooting, how did they manage to build a roster of some of the worst free throw chuckers imaginable? That’s how this game got from the 10-11 point margin to 15: Baylor made 17 of their 20; Utah, 12 of 20.

The player on this roster with the most career free throw attempts, as of today, is Ezra Ausar. He’s a career 60.9% free throw shooter on 517 attempts. Not awful, necessarily, but clearly below-average. He actually beat this average in 2024-25 by shooting 62.4%, but against Baylor, he goes 5-11, which frankly isn’t that abnormal for him.

Ausar technically missed more free throws than anyone else - 74 - but I wouldn’t describe him as the main offender. Lawson Lovering, Utah’s seven-footer and starting center, was a career 43.5% shooter from the free throw line who shot 39.8% from it this past season. When your starting frontcourt averages a hit rate of 52.5% from the free throw line, it becomes hard to overcome elsewhere, particularly when the pair are #1 and #2 on your team in free throw attempts.

Remember when we noted all the dunks, the height, the general tall-ball that Utah built their foundation on? Perhaps it was just a little too much. Of Utah’s top six scorers, five were forwards or centers; only Gabe Madsen landed among them as the clear standout scoring guard. They simply couldn’t find a second option in the backcourt that worked for long stretches.

You can see how this would’ve worked, even with just slightly better shooting. A version of Utah that shoots 67% from the free throw line - barely good enough to be 330th in America - adds 21 points to their season total, which would have been quite important against both Mississippi State (lost by 5, lost FTs by 16) and Cincinnati (lost by 10, lost FTs by 14). Consider that at the time of firing, the Utes were 15-12, 7-9 Big 12 with a WAB of -1.7. A team record of 17-10, 8-8 Big 12 probably has them squarely on the bubble, not far away from it.

Or, hey, what if they’d shot that 34.4% number? That gives Utah 14 more threes, or 42 more points. I imagine that would’ve been pretty useful against, you know, Saint Mary’s (lost by 9, outscored from three by 9)…or West Virginia (lost by 11, outscored from three by 9)…or, well, even this Baylor game, which would’ve shortened the margin down to about six points.

You total all that up, and this slightly improved version of Utah is 63 points better, or around 2.3 points per game. Utah had just two losses by two points or less, both of which were post-firing and one of which was in the Crown, so I’m not sure those apply here. Still, we know points aren’t applied evenly. A Utah team that has wins over any or all of Mississippi State, Saint Mary’s, Iowa, or that final UCF game might have experienced a completely different set of outcomes.

Sometimes, you can do a lot of things right, and it still won’t go the way you desire. Such is life.

I don’t know if Craig Smith has seen The Rehearsal. Really, I have no idea what he’s doing now. There has not been any public indication that the guy who owns South Dakota’s best-ever Division I season, owns one of two (2009-2011) back-to-back-to-back top-50 KenPom runs at Utah State, and beat the KenPom preseason projection in his final two years at Utah has a job anywhere. He may be taking a year off. Even inquiring with our man Trilly Donovan led us nowhere, as he couldn’t find anything new out about Mr. Smith.

Still, given the most free time he’s possibly had in 30 years, maybe he should watch a few episodes. I do not advise that he attempt to describe what he’s watching to anyone unfamiliar with the show, lest he sound like someone bound for an asylum. (From experience.) The conceptual gist is that if you simulate everything in life long enough, you’ll be prepared for anything that can happen, good or bad. No alarms and no surprises. It is much, much stranger than that, and you are forced to reckon with how much or how little of what’s happening is real, but just stick with the base and you’ll be fine.

Anyway, I bring this up because of this particular sequence in the first episode of the show from 2022.

This is the worst possible outcome of the simulation: every possible thing ruined and your time being up. Prior to this, we see the very best outcome of the simulation: learning everything ahead of time so you are prepared to bat 1.000.

Sometimes, you do bat 1.000 with what you’re running and everything goes right. You can ask the eight teams on that SSQ of 1.06 or greater list who finished with record years offensively. Alternately, look at this list once more.

Utah, and Craig Smith, lived out the worst possible simulation. They were the biggest loser of trivia night. No previous team in 25 years put up the core stats they produced - a 2PT% gap of 5% or better, an OREB% of 33% or higher, and a boatload of assists - and failed to win at least 20 games or 71% of their scheduled fixtures. This year’s UConn team set a new low of sorts, but even they won 69%. Nobody is in the same stratosphere as Craig Smith’s Utah Utes were.

Of course, most teams don’t shoot as poorly from the free throw line as they do…well, most. Utah’s 64.1% FT% for 2024-25 is the worst on that list. Second-worst is 2000-01 Kansas, who made almost 100 fewer threes, shot 65.9% from the FT line, and committed 123 more turnovers. Their reward: a 26-7 season and a Sweet Sixteen run. If you extend the search back to 1990, you can find 1997-98 Pacific, a team that shot 61.5% from the free throw line but won 2PT% by 14% a night on average. That team went 23-10, though obviously in a lesser league.

Frankly, all you might have to do is look at Craig Smith’s own career. From 2015 through 2023, his first nine seasons in college basketball, none of his teams shot worse than 70.1% from the free throw line. In 2023-24, an otherwise-quality Utah offense shot 65%, which felt like a blip at the time. Simultaneously, said offense had the highest eFG% of his coaching career. This year’s team posted the second-highest 2PT%, the third-best eFG%, the second-highest OREB%. Even when we simulate long enough, the very worst possible thing is indeed still possible. (The entire second season of The Rehearsal is about this.)

The interesting follow-up to all of this is the reasoning for the firing itself. Smith’s buyout was just $5M, which sounds like a lot until you hear of some of the massive buyouts paid out in this sport. Smith’s replacement, NBA assistant Alex Jensen, has brought with him significantly greater connections and a boatload of NIL money ready to be spent. The result is a roster projected by Hoop Explorer as the 77th-best in the sport, or precisely one spot below Smith’s team when he was let go.

Now, while this post has been pretty defensive of Smith’s system, there were some obvious flaws here. The lineup usage here was frankly pretty bizarre. The starting five of Madsen/Sharavjamts/Wahlin/Ausar/Lovering graded out as Utah’s 8th-best out of 16 qualifying lineups, which is not disqualifying in its own right but probably should be when I tell you it was Utah’s third-worst offensive lineup. In all, Utah seemed oddly committed to Lovering, a horrific free throw shooter who profiles mostly as a defensive specialist, alongside Miro Little, miscast as a lead guard.

When I went through the team myself, I tried to think of what lineup I might have run with. Clearly, Keanu Dawes and his +7.3 BPM should’ve gotten more time. I liked Madsen and Ausar, and Sharavjamts continues to have his moments it would’ve been smarter to pair the other Madsen (Mason, a 38.2% 3PT shooter) or Hunter Erickson (invisible on O, but a very good perimeter defender) with Gabe Madsen. The lineup I landed on as my preference was the two Madsens, a frontcourt of Ausar and Dawes, and Jake Wahlin, an ideal stand-on-the-perimeter-and-rip 6’10” guy who shot 35% from deep and rated out well defensively. These were the projected stats for it, via Evan Miyakawa.

This lineup was used once for three possessions and never again. The same lineup but with Erickson instead of Mason Madsen (+21.46 per 100 instead of +21.49) got one possession of use. The lineup featuring Miyakawa’s five highest-rated players on the team - Sharavjamts, Little, both Madsens, and Ausar - had a projected net rating of +22.98 per 100 with projected shooting splits of 50.6% 2PT/35.3% 3PT/70.2% FT%. Used for two possessions, never touched again. I would declare it ‘less than ideal’ that of the 16 possible lineups with a projected Net Rating of +21 or better per 100, 13 got fewer than 15 on-court possessions.

So: the lineups weren’t good. Still, the system produced these great numbers despite that, and our friend Jon Fendler’s ratings had quite the take on the firing when it happened.

What this leads to is its own interesting simulation. Is Smith content with a year on the sidelines after 29 uninterrupted in coaching? If not, the principles he has at hand - a mathball style that creates a lot of opportunities at the rim, particularly against overly aggressive units that hedge a lot - could be quite the fit as an offensive coordinator for a roster. It’s not as if we haven’t seen a Mountain West alum do exactly this for a title contender.

It’s also not like there’s schools with good defenses that don’t need someone to run their offense. Of the top 25 defensive coaches over the last four years, per Torvik, seven - T.J. Otzelberger, Brian Dutcher, Kevin Willard, Jamie Dixon, Steve Pikiell, Mike Rhoades, and Chris Jans - pair these defenses with offenses ranked outside of the top 50. It wasn’t long ago that Grant McCasland had overseen three straight top-50 defenses at North Texas without any of those being paired with an offense ranked higher than 70th. After hiring Jeff Linder as OC, Texas Tech had their first top-10 offense since 1997.

The system is good. Perhaps better players, more money, and better roster fit would’ve kept him his job. We’ll never really know. The least we can do is not treat one season as an absolute, and instead think of it as a slice of a larger pie. Great ingredients may not make a great P5 HC, but they could make one hell of a coordinator.

One more piece of context that feels relevant: Utah hired an NBA assistant with NIL money at his back...just a year after its biggest rival did the same. Smith was fired one month after his rival dropped a bag to sign the biggest recruit either school could ever dream of signing.