What We Talk About When We Talk About Basketball Statistics: A Glossary

an attempted survey of the nerd landscape

I’ve been asked to do this probably 20 times in the last 2-3 years, but either haven’t had the time or have straight-up forgotten to do it when I have had time. So, with the holiday weekend in full swing and a rare no-work Monday ahead, I figured I’d tackle this.

This is broken down into five sections, starting with the equivalent of the suggested reading section and ending with the most esoteric/unexplored stuff that’s out there. I don’t expect this to be comprehensive for everyone frankly; this is just an attempt to give a proper survey of what I use and potentially share some new stuff with people who either want to understand it and/or are interested in learning more.

SYLLABUS: THE WHO

These are ten websites that I’m using no less than weekly to run this site. They are as follows:

KenPom dot com is the site where basically everything in college hoops analytics originates from. It’s run by Ken Pomeroy, a former meteorologist (!). We’ll get more into the actual stats from the site later, but the gist is that nearly every single college basketball broadcast in a given season will reference his website and its advanced analytics. ($22/yr)

BartTorvik dot com is like Midwest KenPom, run by Bart Torvik, a Wisconsin graduate and Chicagoland (I think?) lawyer. Whereas Ken’s site uses an adjusted margin of victory, Bart’s uses Ken’s older formula of a 0-1 percentile level you’re performing at; it means “how many times out of 100 would you be expected to beat an average D-1 team,” basically. Tennessee’s is 0.9609 as of writing, which means they’d be expected to beat a median D-1 team a hair over 96% of the time. (free)

Haslametrics is sort of like the former two, but focuses less on the Four Factors (which we’ll get into) and has a lot of fun stats, such as how frequently you score after offensive rebounds or steals. (free)

Her Hoop Stats is the closest thing the women’s game has to a KenPom or Torvik and is an indispensable resource when doing research on WCBB. ($50/yr)

Shot Quality is a unique site by Simon Gerszberg and company, which aims to provide a measured quality of each shot and possession taken. ELI5: this website is about the process more than the result. (some free, but minimum of $79/team, $1,500 full package)

Hoop-Math offers the most comprehensive play-by-play database I have found. This is where I get all of the numbers for how teams shoot at the rim, from midrange, in transition, etc. ($15/year)

Hoop-Explorer is a lineup data site similar to the former Hoop Lens. You’re able to plug in a player or players on a team, see how they perform with and without those player(s) on the court, and compare and contrast with other lineup options. You can also split the samples by top 50 opponents, top 100, etc. It’s genuinely brilliant. (free)

Synergy is the most famous resource in college basketball. Nearly every Division I team uses it if not all. They offer video of basically every shot taken in a basketball game in America, along with manual charting and nationwide leaderboards unlike anything else out there. ($30? I think?/year, but $Texas for the good stuff unless you’ve a connection)

EvanMiya is a newer site from Evan Miyakawa that’s sort of like a hybrid of KenPom and Torvik. His site is extremely useful in finding how an injury may affect a roster’s game-to-game performance, along with the tremendous Kill Shot metric, which tells you how many 10-0 or greater runs a team gets or gives up. ($30/year)

CBB Analytics, finally, is where I get all the shot charts from. It’s also just a pretty useful site from Nick Canova that gives you said shot charts, possession start and stop data, where teams get the majority of their rebounds from, etc. (free-ish, starting to move into paid work)

STATS 101: THE BASICS

What I am doing here is assuming you know some fairly basic statistics: field goal percentage (how many shots you’ve made divided by how many you’ve taken), three-point percentage (same but for threes), free throw percentage (same but for free throws), and various counting stats like rebounds, assists, points, whatnot.

The below stats are ones you’ll hear referenced on most broadcasts. Unsurprisingly, most are via KenPom.

Possessions, or Pace, or Tempo. All three of these mean the same thing for discussion purposes. Possessions are meaningful because they are defined in multiple ways: KenPom and most analytics sites define a possession as the entirety of the time a team has the ball without the other team having it. That may sound basic, but that INCLUDES offensive rebounds, a tied ball, a block out of bounds, etc. Synergy counts all of those as starting a separate possession, as do some coaches. It’s ultimately up to personal preference, but I prefer Ken’s definition to Synergy’s.

Efficiency Margin is a very simple thing: against an average Division I team, how many points would you be expected to outscore them by over a 100-possession game? No game in college hoops is 100 possessions sans multiple overtimes, but the gist of KenPom is that it’s tempo-free, meaning that pure points per game scored/allowed really doesn’t tell you the whole story. The pace of the game matters just as much. Which leads you to

Offensive Efficiency. This is a two-parter. Let’s say you had 69 possessions in a basketball game, because, well, obviously. Then, say you scored 76 points on those 69 possessions. Divide 76 by 69 and you get 1.101 Points Per Possession, or PPP.

Defensive Efficiency is the same thing but for offense. Let’s explore points allowed here. One team gives up 56 points per game; the other gives up 64. Naturally, you’re inclined to believe that the 56 PPG defense is superior. However: the 56 PPG defense plays at a 60-possession pace on average, which equates to 0.933 PPP allowed. The 64 PPG defense plays at a 70-possession pace on average, which equates to 0.914 PPP allowed. The team that’s giving up more points per game is the better defense, because they’re allowing fewer points per opportunity. That’s what we’re getting at.

Here’s a three-parter: Adjusted Efficiency Margin (AdjEM), Adjusted Offensive Efficiency (AdjO), and Adjusted Defensive Efficiency (AdjD). These are the above, but adjusted for Strength of Schedule. Games get weighted differently depending on the time of year, but for example, if you play the 50th-rated team (example: +14.0 AdjEM) and you are the 25th-ranked team (+18.5) on a neutral floor, you would be expected to beat this team by 4.5 points over 100 possessions.

The Four Factors were created by Dean Oliver long ago in an attempt to determine the four things that can truly swing a basketball game. In descending order of statistical importance, they are:

Effective Field Goal Percentage (eFG%). What this is is an equation: (Two-Point Made Field Goals + (1.5 * Three-Point Made Field Goals)) / Total Field Goal Attempts. It’s better than normal FG% because it gives you the appropriate added value of a three-pointer being worth 50% more than a two. An average eFG% is about 50%; a good one (top 100) is 52%; a great-or-better one (top 50) is about 54%. Due to shooting variance, single-game eFG% can be wild; I have seen teams post 70% and 30% in the same season. Based on research done last year, this accounts for approximately 50% of offensive efficiency.

Turnover Percentage (TO%). This is however many turnovers you’ve committed divided by the overall amount of possessions. The average team sits at about a 19% TO%; if you’re at 17% or lower on offense you’re doing pretty well. Defensively, if you’re at 21-22% or higher you’re really cooking. This accounts for about 25% of offensive efficiency.

Offensive Rebounding Percentage (OREB%). This is determined as follows: your team’s OREBs divided by the other team’s defensive rebounds. As an example, if you get 7 OREBs and the defense has 27 defensive rebounds, you rebounded 7 of your 34 missed shots, AKA a 20.6% OREB%. The average team sits around 29%; the good rebounding teams are at 32% or better. This is worth about 20% of offensive efficiency.

Free Throw Rate (FT Rate). This frequently gets confused on Twitter for Free Throw Percentage, which is not the same thing. This is Free Throw Attempts divided by Field Goal Attempts; a team that has 21 free throw attempts and 54 field goal attempts has a FT Rate of 38.9%. The average is around 31%; a good-or-better FT Rate is 35% or above. This very rarely decides a game unless it’s a huge margin in favor of one team, as it sits at being worth 5% of offensive efficiency.

STATS 201: THE SYNERGY SECTION

These are either stats that don’t get referenced as much on broadcasts or stats that don’t get referenced enough, but are still important to telling the story of a basketball game. It’s broken down into two sections.

Synergy Sports is the website I use for every single article I write here. As mentioned before, it’s got all of the video anyone could ever need to go along with manual charting that verifies “this happened and this is how this happened.” It’s stats and video, which really hits the golden mean as a basketball fan.

Generally, when I reference Synergy stats it’s in a variety of ways. Two of these can be noted up top:

Percentile rankings. A lot of times in posts I’ll say that Texas (to pull a name out of thin air) has, I don’t know, a half-court offense that ranks in the 79th-percentile. What this means is that, unadjusted for schedule, Texas’s offense is more efficient than 79% of all other Division I teams. Alternately, a team could use post-ups more than 97% of all other Division I teams, meaning they’re in the 97th-percentile of using that play type.

Percentage of team possessions. Pretty simple: let’s say that 9 of a team’s 75 possessions end in a post-up. That’s 12%. I can say, using the Synergy data, that 12% of your possessions ended with a shot off of a post-up.

Those are the basic ones. The others are split into two sections: play types and shot types. Because it’s a holiday weekend, I’ve linked a short video showing that play type or shot type that you’ll be able to click on. (Easter egg: the player represented is the national leader in points at that play type or shot type in Division I, whether it’s men’s or women’s basketball.) I’ve also noted where these shot types rank in efficiency at the bottom of each list.

PLAY TYPES

Transition is a little tough to define, but my general definition is any shot attempt within the first 10 seconds of the shot clock. Some consider it in the first 7-8 seconds, but 10 is a little easier to go with, and few defenses get fully settled in that time frame. A key thing to know is that this and Fast Break Points are pretty similar in that they DO NOT develop from a dead ball or out-of-bounds play. This is live-action, often developing from steals or missed shots. (Ta’Niya Latson, Florida State.)

Isolation is a 1-on-1 scenario that could start via any number of things, but generally, the image in your mind is of a guard or forward clearing a driving line or an entire side of the floor to get past their defender. This is generally the least or second-least efficient play type depending on the season, but it is also the coolest when it’s working, so who’s to say. (Noah Thommason, Niagara.)

P&R Ball Handler is, well, the ball-handler in any pick-and-roll situation eventually either taking the shot, getting fouled, or turning it over. This trades places with Isolation for the least-efficient play type in a given season because they’re extremely similar things: players going one-on-one or even one-on-two to get theirs. (Sam Sessoms, Coppin State.)

P&R Roll Man is the guy setting the screen. There’s a variety of ways this can look: you can slip the screen, which is like faking a pick; you can roll to the basket, which I imagine you know what that looks like; you can pop out for a three, which is tough to defend if you’re not ready for it. (Jack Nunge, Xavier.)

Post-Up requires no explanation, presumably. You know what a post-up looks like. This used to be the most popular play type a long time ago, but it’s faded from its perch except for teams either determined to use it or who roster a literal giant. However, post-ups are a little unusual and do require some explanation in that Synergy tracks a few different kinds:

Left Shoulder is when a player turns over their left shoulder, AKA what looks like spinning to the right. (Josh Cohen, Saint Francis (PA)).

Right Shoulder is the reverse: over the right shoulder, spinning to the left. (Zach Edey, Purdue.)

Post Pin is a pass that’s over the top of the defender, generally from the point. The post player pins the defender with their body (usually their butt!), and when these passes are on point, it’s basically impossible to stop from scoring. (Monika Czinano, Iowa.)

Face-Up is when a player stares down their opponent instead of spinning, dribbling, or turning. These can be jumpers, but it generally results in a drive to the basket rather than a true post-up. (Drew Timme, Gonzaga.)

Spot-Up comes in two kinds: an actual spot-up, which is a guy taking a catch-and-shoot three, and a spot-up that results in a driving lane where a player fakes a shot then goes inside. Much more of the former happens than the latter. In our current era of college hoops, this is the most frequently-used play type and right at the midpoint of efficiency. (Alex Ducas, Saint Mary’s.)

Off Screen is something that every Tennessee reader will be familiar with. These are off-ball screens that directly result in a shot attempt. Every team in America runs off-ball screens to some extent, but there are a proud few that run them like crazy, such as Tennessee, Davidson, and South Florida women’s basketball. (Myles Stute, Vanderbilt.)

Hand Off is a play type that largely happens on the perimeter, largely of the dribbling variety. What this looks like would be really familiar to you if you remember Loyola Chicago beating Illinois in the 2021 NCAA Tournament: a post or larger player dribbling on the perimeter as a guard flies around, takes the ball, allowing the post to set a quick screen. It’s like a pick-and-roll/off-ball screen hybrid, but generally less successful than Off Screen. (Jordan Dingle, Penn.)

Cut takes place in a variety of forms, but most commonly in college hoops it’s a late cut to the basket from a post player or particularly fast guard. There are off-ball screens that result in basket cuts, generally from out-of-bounds plays but occasionally from live action. Also, there is the “flash” cut, which is generally when a player flashes to the middle of a zone defense. Unsurprisingly, for a play type that takes place almost exclusively within 10 feet of the rim, this is the most efficient play type in the sport. (Madison Siegrist, Villanova.)

Putbacks are exactly what they sound like. (Angel Reese, LSU.)

Miscellanous is not one that’s ever referenced, but if you think of a possession that looks like seven-year-olds reacting to a fire drill, you’re on the right track. (Hannah Simental, Northern Colorado.)

Ranking of these play types in terms of efficiency:

Cuts

Putbacks

Transition

P&R Roll Man

Spot-Up

Off Screen

Hand Off

Post-Up

Isolation

P&R Ball Handler

Miscellaneous

So! Those are the play types. However, Synergy also offers some interesting ways of defining shots that I reference pretty frequently.

SHOT TYPES

I don’t think I need to define a layup/dunk/etc. for this audience, but we reference a couple of things really frequently here. Let’s get into it.

Catch and Shoot attempts are shots that require zero dribbles to get off. You’re thinking of the platonic ideal Klay Thompson attempt as I type this, I assume. The average hit rate of these are around 34-35% in a typical season, which is a little above the overall 3PT hit rate of 33-34%. This goes into two specific divisions:

Unguarded catch and shoot threes are what they sound like: open threes where a defender isn’t within 4-5 feet of the shooter. In real time, you might think that 80% of three-point attempts look open, but that really isn’t the case; it’s more like 45-50%. Average hit rate in 2022-23: 37.4%. (Sammie Puisis, South Florida.)

Guarded catch and shoot threes are the opposite: the shooter at least has a hand in or near their face, and while they still may hit the shot, there’s a real closeout being attempted here. As mentioned above, an unguarded and guarded three may not look that different in real time, but I promise that if you slow the game down, you can tell the difference, like, 90% of the time. Average hit rate: 32.1%. (Darius McGhee, Liberty.)

Jumpers Off the Dribble, or Pull-Up Jumpers, require at least one dribble to be classified as such. Some of these are mere formalities - a player pump-fakes on a defender closing out hard, takes one dribble, and shoots - but more frequently, these are threes after 2+ dribbles. The thing you’ve got to remember is that the average pull-up jumper is probably taken by a better shooter than the average catch-and-shoot three is. Still, the numbers don’t lie; the average hit rate on these from three in 2022-23 is just 29.7%. Every dribble lowers your expected hit rate, unless you’re an elite shooter. This is why nearly every Tennessee preview talks about forcing pull-up Js. If they hit them, they hit them, minus the elite few. (Antoine Davis, Detroit.)

STATS 301: THE NON-KENPOM SITES

So: there’s a bunch of sites listed in that intro section. I think we’ve exhaustively covered KenPom and Synergy, which are the two main data sources in the college basketball world. (I would include Her Hoop Stats in here as well; it basically is KenPom for women’s hoops and it’s a wonderful resource.) The other seven websites listed haven’t really been covered, so let’s do that here and explain why they’re useful and what specific unique things or stats they offer.

Bart Torvik’s website is one of the better things the Internet has ever afforded humanity, as far as I’m concerned. If you called it Free KenPom, you would not be far off. I don’t love the idea of using the Pythagorean method versus straight efficiency margin, but to each their own.

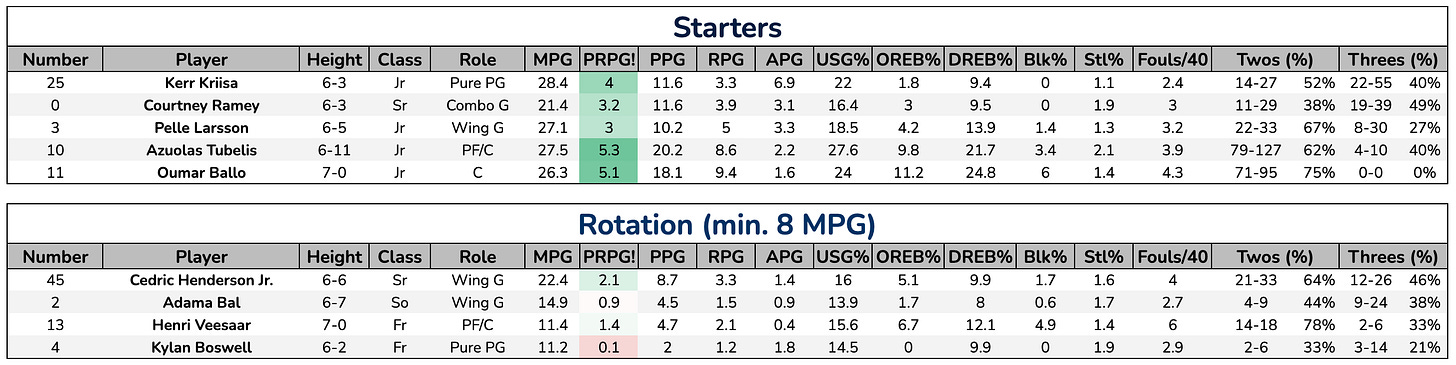

Torvik’s stats populate the lineup charts you see in my previews every week.

Only one of those requires a significant amount of explanation: PRPG!, which used to be called the hilarious PORPAGATU but now is the shortened version. Essentially, this is a one-stop stat (mostly driven by offense) that functions as Points over Replacement Per Game. It’s not perfect, but it gives you a great way of seeing the most valuable offensive player on each team.

Torvik’s site also offers Box Plus-Minus. This estimates the impact a player has on each side of the court - offense and defense - and boils it down to one metric. It’s extremely useful in game prep for figuring out who statistically projects as the best defender (or most impactful offensive player) on a given team.

Along with all of this, Torvik’s site offers NCAA Tournament win expectancies dating back to 2000, a live updating NCAA Tournament forecast, all sorts of graphs, all sorts of charts, etc. I recommend getting lost in it one day.

Haslametrics is an HTML’d out original that I find deeply fascinating.

This is a website wholly uninterested in SEO but very good at creating new, interesting ways of paying attention to a basketball game. The stats I use from this site are:

Free Throw Attempt Rate. This is FT Rate, but adjusted for the opponent and per 100 possessions, not a straight FTA/FGA equation. It is amazingly useful for seeing just how much impact a team has at the line over the course of an average game.

Field Goal Attempt Rate. Meaning here: how many field goals you attempt per 100 possessions against the average opponent. If you pair this with FTAR, you’re well on your way to measuring a true amount of shot volume.

Potential Points on Steals or something like that. What this is: a stat measuring how many field goal attempts you generate in the first 10 seconds after a steal.

Potential Points on Second Chances measures field goal attempts in the first 5 seconds after a rebound.

There’s some other weird ones he has, such as a Consistency metric and a stat that measures how much worse you are away from home, but those are the main four I look at for context.

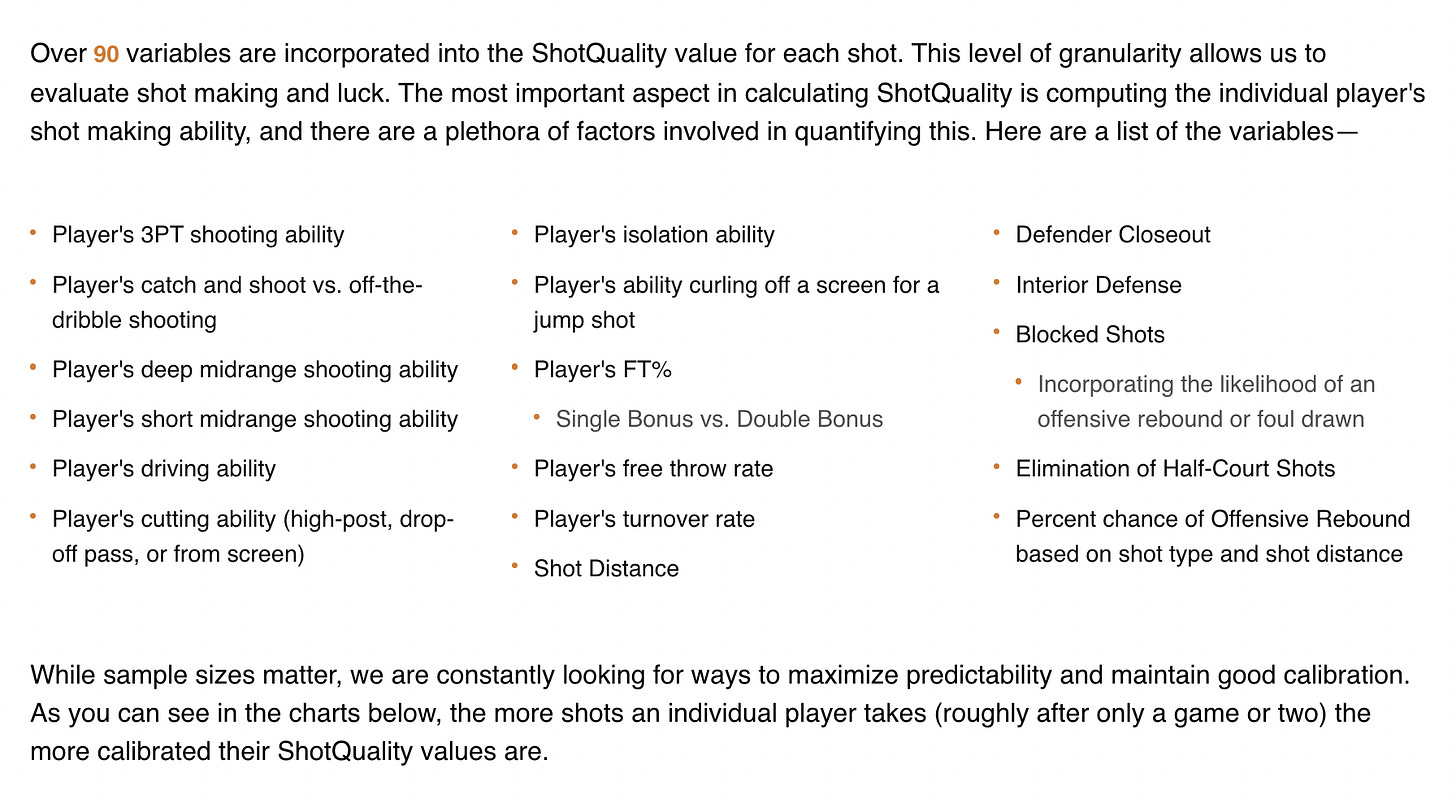

Shot Quality is a proprietary thing from Simon Gerszberg that’s best explained on his own site.

SQ’s refined their formula over the last couple of years and I really do think it’s the best it’s ever been. I look at SQ before every game to see if their data suggests a team has been lucky/unlucky/had an appropriate amount of luck on offense and on defense. There’s also a section that utilizes the Play Type data from Synergy that breaks down the quality of shots the team gets on those plays.

Hoop-Math is another HTML joy that collects all the play-by-play goodies. Everything you see in the Shot Attempt/Shot Efficiency Splits section of these images:

Is via Hoop-Math. They accumulate play-by-play data from every single Division I game across the country, and their site updates daily. It’s a tremendous resource just for doing sanity checks, but for some other stuff:

Shot blocking data. If I ever reference that a team is blocking 17% of opponent attempts at the rim, it’s come from Hoop-Math.

Transition/half-court data. If I ever reference that a team ranks 17th in America in getting shots off in the first 10 seconds of the clock after a missed shot, it’s from Hoop-Math.

Assist rates. Deeper than the KenPom Assist Rate (assists / made field goals), it’s that same equation but for rim/non-rim twos/threes.

Non-rim twos. Loyal readers know we’ve been over this before, but non-rim twos get collected in as mid-range twos just because that’s an easier thing to get across. However, non-rim twos can include a variety of things: jumpers, runners, floaters, even some hook shots.

Hoop-Math is the #1 beneficiary of the Table Capture plug-in I have in Chrome.

Hoop-Explorer is a lineup data site made by a guy on Reddit that has somehow become one of my most visited websites of any kind. Any sort of lineup data, on/off splits, or With Or Without You numbers I have referenced on this website almost certainly have come from this guy. If I post a graphic that looks like this:

It’s from Hoop-Explorer.

I think the on/off splits are useful for obvious reasons, but Hoop-Explorer has four key things that make it stand out better than anything else in the market:

Luck adjustments. They are not perfect by any means, but H-E is the only website I’ve found where you can adjust lineup data or any data at all for 3PT% variance. Shooting variance is an extremely real part of the game, and the average standard deviation of a Big Six team in 3PT% is almost 10% a game. Anything within 23% to 43% for an average team is probably a reasonable outcome. H-E factors that in.

Lineup or player-specific shooting splits. Did you know that when Jett Howard is on the floor for Michigan, the Wolverines take 5% more threes and 5% fewer attempts at the rim than when Juwan’s son is off the court? That’s directly via Hoop-Explorer and is something I use for every single game I preview.

Garbage time filtering. Want to get rid of data that pops up whenever a game is out of hand in one direction or the other? With the click of a button, H-E has this.

WOWY but super specific. Like: did you know that Hunter Dickinson’s Usage Rate jumps from 26.5% with Howard on to a hilarious 39.6% with Howard off? That’s also available on H-E.

I cannot evangelize this site enough; it has saved me an immense amount of time and has made my previews much better. And it’s free!

EvanMiya is the brainchild of Evan Miyakawa. It’s an all-around good website with a lot of useful bits, but this is built around one huge thing: Bayesian Performance Rating (BPR), which is the best metric I’ve found in college hoops at analyzing a player’s impact nationally on both offense and defense, adjusted for schedule. It’s like BPM or any of the NBA metrics if all college teams played the same schedule. I utilize this every single game to figure out the most impactful player an opponent has by Evan’s system.

CBB Analytics, lastly, has a lot of cool stuff on it, but the breadwinner are these shot charts.

STATS 401: FILES NOT YET FOUND

Here’s a collection of things I’m interested in, need more research on, want to look into more, or am in the process of using more but aren’t quite to a good confidence level.

Defensive shot selection. This is a little controversial in the basketball world; some are hard-set on believing that defenses exclusively control shot selection, while some would have you believe there’s no control here at all. The answer is somewhere in the middle. Research shows that the closer you get to the basket, the much more control a defense offers over the quality of the shot. The further out you get, the less control a defense has. Still, I think there’s something to the style of shots allowed on the perimeter. I’d like to explore this more in the future.

What lineup data stats actually make sense. I don’t find individual plus-minus to be that exciting; that’s one player of the five on the court. Sometimes it helps, sometimes it doesn’t. However, I think you can tell a player’s impact by looking at the Four Factors or even at the shot selection while on the court.

How home court affects certain stats. Obviously, we know that points, shooting, and fouls are all influenced by what court you’re playing on. However, did you know that home court has significant influence over your Assist Rate, simply because your home statistician is likely more friendly to you in this regard than a road one? Or that steals are mildly inflated at home? I’d like to explore how this affects even more statistics, but of the non-human error variety. How often do teams get off open threes at home versus on the road? Is there a meaningful difference in shot selection between the two? Does this affect more secondary stats such as the size of your rotation or point distribution between 2PT/3PT/FTs? There’s a lot I’d like to look into.

What secondary stats are/aren’t predictive of offensive rating? We know that shooting matters, obviously. But do we have conclusive proof that more assists = better efficiency? Do we have anything showing that taking more corner threes is conclusively better for offensive efficiency than those above the break? CBB Analytics has done quite a bit of work on this; I’m hoping to get some of it on here soon.

What players have the most shot gravity/are the most effective for spacing. Shot Quality has this data but it’s private, understandably.

A small group of stats I’d like to use more but want to make sure are useful first. I like Hakeem%, which is Steal% and Block% added together. That’s via CBB Analytics. My personal view on this is that it’s a lot more effective as a team stat than an individual one unless for Draft purposes, so I don’t use it very often, but it’s interesting. I’d also like to add splits between short mid-range attempts (5-12 feet) versus longer ones (13+ feet), but the research I’ve done doesn’t show a meaningful difference yet. Lastly, I think there’s something to team-wide experience mattering in March, but that requires more research on my part.

A small group of stats I do not use. Individual plus-minus, because that’s completely uncontrollable outside of your own shots taken/allowed. (Even lineup plus-minus has some problems, though it’s a bit better.) Defensive 3PT%, as Ken Pomeroy’s research shows that a defense has no more than 15-20% control of this on a game-by-game basis. There’s aspects you can control, but largely, it’s luck. Total rebounding margin, a pointless stat because it doesn’t account for the percentage of missed shots you have/haven’t rebounded. (I WILL use combined turnover + rebound margin from time to time, though. That tells a story.) Everything else is more or less on limits.