Hello! This is the start of a new series titled What Went Right (or Wrong), a five-week offseason series about teams that heavily over- or underachieved in 2022-23. This first week is free, but the next four weeks will be behind a paywall. If you reply to me with the phrase “blue check,” I’ll DM you a code that gives you 40% off for a year, aka $18 for a full season (+offseason)’s worth of content.

On the surface, a team that has a nine-win dropoff from one year to the next isn’t that notable. It happens with fair frequency every season, whether due to a coaching change, a roster overhaul, or straight-up performance decline. That aspect of the Louisville story is not notable in its own right.

Every other aspect of this:

Is very, very notable.

The Louisville Cardinals went 4-28 in the 2022-23 men’s college basketball season. I’m typing that fact out because it still feels absolutely surreal to be typing it out. How could a major program fall as far as Louisville has? There have been worse Big Six program performances over the last couple of decades, but they’ve been by teams that aren’t traditional powers (aka, Oregon State and Utah).

While an imperfect measuring tool, Sports-Reference’s Simple Rating System places Louisville as the 7th-best college basketball program in modern history. Among the six programs ahead of them, over the last 50 years, only Indiana’s disastrous Year Zero season in 2008-09 - a 6-25 death rattle - comes anywhere close. Even then, the recruiting profiles of those on the first Tom Crean roster:

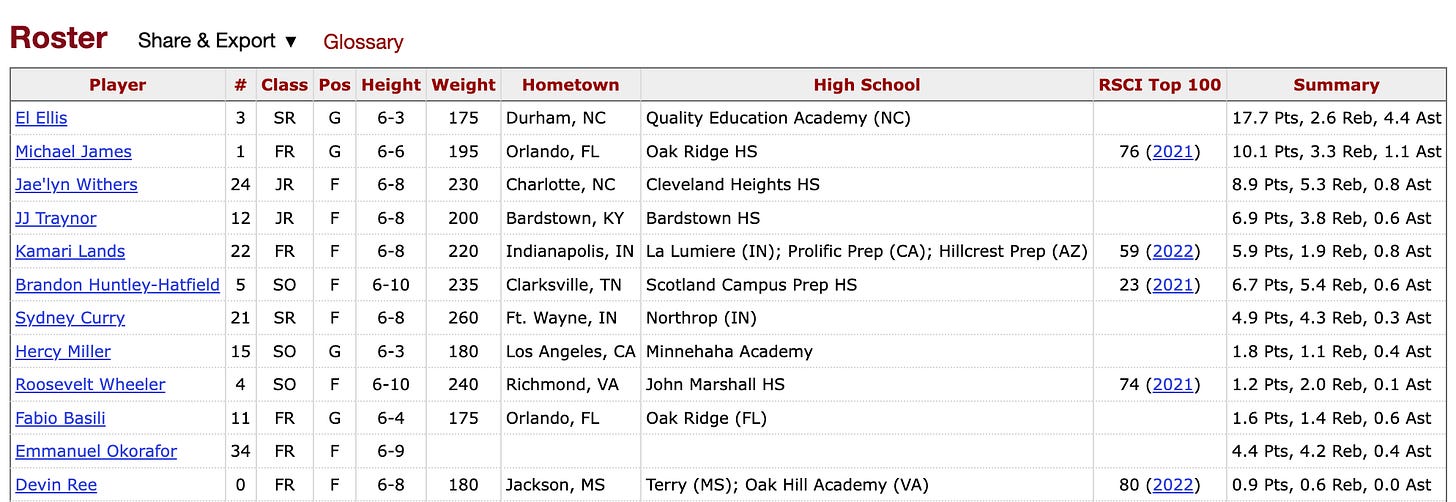

Is nothing close to what Louisville had, at least in terms of on-paper talent, entering this past November.

In terms of pure, uncut disasters, this was probably the worst season I have ever seen from a college basketball team since I’ve been an invested viewer (2002 or so). Louisville’s previous worst KenPom ranking in the 25-year history of his site was 133rd; they blew past that by a full 157 spots.

So: how did it get this bad? Instead of just a normal Year Zero situation under a brand new coach, how did this develop into possibly the very worst on-court performance in modern history? Instead of one or the other being bad, how did Louisville’s offense and defense collapse beyond reason? Is there any path out of this? As best as I can, we’ll examine the wreckage.

Step 1: Foundational collapse

As neat as it would be to put a bow on it by saying Kenny Payne is objectively the worst head coach in the nation, I don’t think that’s necessarily true. To be sure, not all of what happened this past season was his fault. This starts before Payne.

Rick Pitino was fired from his position as Louisville’s head coach just three weeks before the start of the 2017-18 season. In his stead came Chris Mack from Xavier. Mack was, on paper, the perfect hire: a guy who’d already produced excellent results at Xavier and was deeply familiar with the recruiting area Louisville generally works in. Through one season, and even through two, it looked like the marriage would work. Then came 2021-22, and everything went from fine to disastrous.

Mack only made it through that January 24 game against Virginia; he was fired immediately after. For a variety of reasons, including that Mack and the Louisville fan base never seemed to fully gel, Louisville wanted to hit the reset button. By doing so, they found themselves in a unique situation after the season: a wide pool of potential hires, some with reasonable connections to the university itself. The choice from influential alumni was Payne, a former Kentucky and New York Knicks assistant.

Payne had never been a head coach, and most Louisville personnel seemed to understand it would take a little time for things to work out. Add in the fact that various NCAA judgments were still hanging over Louisville’s head, and it makes sense why this was a Year Zero situation regardless of who Louisville would’ve hired.

And yet.

Entering the 2022-23 season, Payne’s roster had that on-paper talent listed above. That’s one thing. The issue is that said roster had zero point guards on it. The career high of any player on the roster, in terms of assists per game, was El Ellis. He posted 1.6 assists per game the previous season.

Before the season even began, Louisville had failed in this specific regard to set themselves up for success. Even beyond that, the roster was a mess. JJ Traynor, a power forward under the previous regime, became a 3. Jae’Lyn Withers, a small-ball 5, became a 3/4. Brandon Huntley-Hatfield, a center, played all of small forward, power forward, and center. The team had length, they had athletes, but no cohesive plan whatsoever. It showed.

Step 2: An offensive offense

Sorry, too easy.

Not that 2021-22 Louisville was the greatest team in human history, obviously, but even a team that shot 31% from three was better than what the 2022-23 edition came up with. The final Chris Mack production did have a point guard on the roster. Mason Faulkner was by no means a special athlete, coming over after four years at Western Carolina, but he was a point guard that could run whatever offense you would say Louisville were trying to run.

Faulkner’s assist rate of 26.2% was nothing special, and indeed it was eclipsed by El Ellis’s 30.8% despite Ellis playing out of position. The problem was everyone else. The next-highest assist rate among rotation members (8+ MPG) was 8.1% from Kamari Lands. The next-highest assist number was 1.1 per game. Guard play was…erm, lacking. I guess that’s the nice way to put it.

Louisville’s general offensive goal was to play a half-court oriented style that worked the ball inside first, whether by Ellis penetrating or getting it inside to a post player. The problem when you don’t have good guards or good off-ball movement, aside from literally everything, is that possessions frequently get bogged down. Louisville found themselves in the final 10 seconds of the shot clock more than almost anyone else in ACC play, and rarely were they able to produce something constructive when the clock wound down.

El Ellis was forced to play 36 minutes a night because there simply wasn’t another option for any half-court offensive success whatsoever. He couldn’t be as aggressive as I’m guessing he’d prefer on defense, either, because he had to be out there. Foul trouble wasn’t on the table. No one else stepped up to help him, which should’ve been something the staff foresaw in August. But hey.

Teams survive every year without a true point guard or a point-by-committee situation, but the reason it works is that there are multiple options. If you don’t have a true PG, you make one up by having multiple ball-handling guards and wings on the roster. Alternately, you have a guard that can hit jumpers with frequency even if he’s not a great passer. (Ellis shot 32% on mostly guarded threes.) Louisville waltzing into the season with one option - a guy who’d never done it full-time before - and expecting anything other than pain was a choice.

Step 3: Defensive disaster, top to bottom

The remarkable thing about this Louisville team is that the offensive was the better unit. It really wasn’t close. The offense finished 251st in KenPom’s Adjusted Offensive Efficiency rankings; the defense, 312th. When your stats chart on Ken’s site looks like this, you’re gonna have a real bad time.

It’s worth noting that this is genuinely a historical achievement for a Big Six school. Just twice in the last 15 years has a team from the top six conferences in college basketball finished in the 300s in defensive efficiency; only 2021-22 Oregon State (320th) came out worse. Even then, it’s Oregon State. It shouldn’t be Louisville, a team that has won a championship (whether the NCAA wants you to believe it or not) in the last 10 years.

Kenny Payne’s main thing over the last two decades has been quality big men. He’s developed quite a few of note at Kentucky and was generally recognized as the center whisperer of sorts. That could be why this first team of his was as large as it was, the 12th-tallest team in Division I. It makes it that much more confounding that they finished 353rd (!) in FG% allowed at the rim.

Louisville not only gave up one of the 11 worst hit rates down low, they also gave up more rim attempts than 71% of college teams. That meant Louisville gave up 28.7 points per game at the rim, in line with schools like East Carolina or Western Illinois, which are not Louisville.

For all of Louisville’s height, it stems back to the guard issue first. El Ellis was the only player on the entire roster that could somewhat feasibly play point guard. In Louisville’s system - which was mostly a man-to-man with an occasional press and/or zone elements - the Cardinals would generally hedge hard on ball screens and force the ball out of a guard’s hands.

This is a fine strategy on its face, but what happens when you only have one guard on the entire roster is that said guard cannot be aggressive defensively, lest he land himself in foul trouble and tank the game before it even begins. When Ellis cannot be a ball-stopper, you’re then reliant on your bigs to recover in time in ball screen sets. Louisville’s bigs are big, but they are not very fast. So you get a lot of this:

Louisville’s ball-screen defense ranked in the 2nd-percentile nationally and 357th overall. Their contemporaries were sides like UC San Diego and Delaware State, which, again, are not Louisville.

However, this wasn’t just a system issue or a personnel issue. It frequently became a focus issue. Often during games, one would notice a Louisville player just…fall asleep in the middle of a play. This is perhaps why the Cardinals ranked 347th (!) in defending cuts to the basket, many of them not requiring any special action at all. I would love to hear from a staff member, a roster member, or God Himself what exactly was the plan here.

If you are a Louisville fan and you made it to this part of the article, please contact the U.S. government for your war medal.

Step 4: The uneasy path forward

For some, it was at least a mild surprise that Kenny Payne was given a second chance to turn things around. A 4-28 season at Eastern Kentucky, for example, is obviously bad, but you can frame it as a rock bottom rebuild at a place that’s not easy to build at. A 4-28 season at Louisville is an unmatched disaster that would normally result in a complete top-down wiping of the program. It’s a death penalty year by a different name.

For Payne, a Louisville alumnus and the person the search committee wanted most, it’s a different story. Was 2022-23 an unmitigated horror show? Obviously. Is it the end of the program? If all goes according to plan, it shouldn’t be. Payne did pull in a top-10 recruiting class with four 4-star recruits in it. Are those obvious lottery picks that can instantly turn Louisville around? No, but they’re at least evidence of a plan going forward.

And yet: I still have a lot of worries here. Much of Louisville’s 2023-24 ceiling, at the time of writing, depends on a pair of guards: Mike James (a returner) and Skyy Clark (an Illinois transfer). Both James and Clark functioned as combo/wing guards last season; neither have any serious experience as a point guard at the college level. Clark played point in high school, but he played a total of 10 possessions at point for Illinois last season because he was a turnover machine.

Aside from Clark, Louisville doesn’t currently have another point guard. James was arguably Louisville’s best non-Ellis piece last season, but he isn’t much of a ball handler. The lineup should look more functional, but at this moment in time, I’m continuing to question what Payne exactly is building. Projection sites aren’t that friendly, either; Torvik has the current Louisville roster ranked in the 150s, which would admittedly be a huge leap forward but still isn’t capital-L Louisville.

So: what’s it gonna be? Will Louisville learn from their program-wrecking mistakes, or will this simply be a continuation of the disaster? What defines a successful Year Two of Kenny Payne? What, if anything, can the staff do to get the most out of what they’ve assembled? What will they change? Rarely do I write these and still have more questions than answers at the end, but such is the Louisville quandary.

Imagine, if you will, writing about this team through the last 2 seasons. Sigh.