Hello! This is free, but as of now, it’s likely the last or next-to-last free post of March. Consider signing up now for just $20 for a full year and get all the March Madness goods, including bracket advice, survivor pool advice, life advice, quality analysis, and the works.

On with this very-fun-to-write show about some famous near-misses.

Each March, we let winners write the story. The champions, obviously, but also those who get deep and weren’t expected to. The NC States, Florida Atlantics, Saint Peter’s, Oral Roberts, Loyola Chicagos, VCUs, George Masons, and Butlers of the world. The also-rans who got to run for two beautiful, delirious weekends in spring.

What we never, ever discuss is those on the flipside of these equations: the teams they defeated early on that could’ve written these same stories themselves. I have a database of tournament odds and numbers that goes back through 2002, which I’m only bringing up for this reason: I have the ability to see just how unlikely certain runs were based on the pregame odds.

In the spirit of March, and the spirit of the large weighted coin flip that is the NCAA Tournament, I went hunting for the five coin-flippiest deep runs in history: those who had to overcome a true 50/50 game in the first round (alright, somewhere between 48/52 and 52/48), a game that finished with a scoring margin of three points or less. There’s more of these than you may think, but over the last 23 years, five cases have stood out from the field. They’re separated by how far they advanced, and how shocking the cases themselves were.

Elite Eight

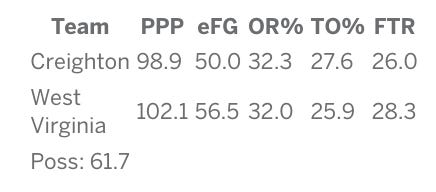

2005 7 seed West Virginia (48.6% odds to make Round of 32, 5.9% to make Elite Eight)

THE VICTIMIZED: 10 seed Creighton (lost 63-61).

In the spring of 2005, a famous refrain began to rattle around college basketball: you got Pittsnogle’d. Star forward Kevin Pittsnogle went on a historic run, scoring 18 PPG, draining 13 threes, and pulling off clutch play after clutch play. A March Theory I have is that you need at least one odd-looking white guy playing serious minutes to go deep in the Tournament. Pittsnogle certainly filled that.

And yet: he was two points and perhaps one foot away from being a mere footnote in the history of the Round of 64, let alone modern college basketball.

THE COIN FLIP: A tipped shot and one extra foot.

In the first round of that tournament, West Virginia tangled with a very good Creighton side that had a 23-10 record, overcoming a brutal midseason stretch of poor play to win Arch Madness. In fact, for most of the second half, West Virginia trailed Creighton, only wrestling back the lead with about five minutes to go. With 42 seconds on the clock, guard Nate Funk is called for a blocking foul on a drive to the basket. WVU hits both FTs to tie the game at 61.

Creighton’s next possession can only be viewed by the international Spanish broadcast, which is a fun listen, but two things happen during it. First, Creighton is forced to use a timeout - NOT their final one - while trapped in the corner. Secondly, Creighton gets frazzled into a contested three. The ball is tipped.

In the aftermath of the tip, the ball is rebounded by one Kevin Pittsnogle. In this image, it looks like WVU has about six seconds to drive the ball down the court.

They don’t need all six seconds, because Pittsnogle hits the outlet pass perfectly. Behind the action on camera, Tyrone Sally has beaten the Creighton defense deep. Here’s what occurs next.

Creighton has two seconds left and one last chance to tie the game. Nate Funk, a 47% 3PT shooter this season and 41% for his career, gets off a contested-but-fair look. If Funk were exactly one foot further back in the above video, the shot likely banks in for Creighton to win, 64-63. The shot does not go in.

THE AFTERMATH: You know the story from here. Kevin Pittsnogle becomes a March legend, West Virginia makes the Elite Eight, and no one except Creighton fans or myself remember the names Nate Funk or Johnny Mathies. But what if that last shot isn’t deflected? What if this game goes to overtime?

It’s a little less likely Creighton would’ve won this game in overtime, given that starter Mathies had fouled out. And yet: Sally, the guy who made the game-winning bucket, had four fouls. The game had been so dead-even to this point that a Creighton win in overtime obviously wouldn’t have been unrealistic. Based on pregame odds and a small reduction for no Mathies, we’d probably give WVU a ~52% chance to win in OT. That’s more than 50%, but it’s not 100%. Imagine never hearing or thinking about the name Kevin Pittsnogle. What kind of awful world would that be?

2010 6 seed Tennessee (50.2% odds to make the Round of 32, 7.6% to make the Elite Eight)

THE VICTIMIZED: 11 seed San Diego State (lost 62-59).

It’s been matched last year, but for a long while, Tennessee not only held the standard of being everyone’s Best Program Without a Final Four. They also held the standard of being everyone’s Plausible Best Program Without an Elite Eight. Until 2010, Tennessee had never cracked the fourth round of the NCAA Tournament. In KenPom’s 29-year history, through 2025, Tennessee has had teams finish the year ranked 6th, 9th, 10th, 10th, 13th, 13th, 17th, and 18th. None of those (save for the 2023-24 team that finished 5th) have made the Elite Eight.

Instead, it was the 2009-10 crew, a thoroughly middling 6-seed that entered the Tournament 38th in KenPom and was the 8th-best team in its own region. Only seven 6-seeds since Tennessee have been rated 38th or worse in KenPom. Exactly two of those (2012 Murray State, 2013 Butler) won a game, and neither touched the Sweet Sixteen.

Meanwhile, their first round opponent had this guy.

How in the world did this team become the one that broke through ahead of many, many superior ones?

THE COIN FLIP: An extraordinary case of bad 3PT variance.

Melvin Goins is, by any realistic use of the term, a footnote in college basketball history. He played three seasons of Division I basketball, shot 29% from three, never scored 20 points in a single game, and despite being a 5’11” point guard, he barely had more career assists (215) than turnovers (171). Also, entering this Thursday night in March, he had made one three in his last eight games. He’d attempted six total in the last month of his life.

About 11 minutes in, Tennessee’s shot clock is winding down, and after a near-turnover, JP Prince finds Melvin Goins fairly well-guarded in the corner. Goins puts up the shot because, well, you don’t want a shot clock violation. And:

It goes in. Five minutes later, in transition, Goins dribbles straight into another three-point attempt. That goes in.

Despite this sudden turn of events, San Diego State never quits pounding away, briefly leading with about nine minutes to go. With under a minute to play, they cut it to 57-56. With the season on the line, JP Prince is fouled for a 1-and-1 attempt. Prince is a horrid free throw shooter, briefly going entirely to one side in an attempt to fix his shooting vision. Prince misses the shot…and Tennessee gets the ball back.

This is in the era before the clock resets to 20 seconds, so a full (then) 35 goes back on the clock. Tennessee works the clock down for what seems like forever, and magically, the ball ends up back in Melvin Goins’ hands one final time.

THE AFTERMATH: A major forgotten part of this entire scenario is that there were two games that evening in Providence: this one, of course, but another one that felt at the time like a seismic upset.

Basically, both Tennessee and San Diego State hit the court late Thursday knowing they were 40 minutes away from only having to beat a 14 seed to make the Sweet Sixteen. San Diego State simultaneously had the added pressure of this potentially being their first-ever Tournament win. It had to wait another year. Tennessee smoked Ohio in an uneventful Round of 32 game, then beat Evan Turner and Ohio State in a very eventful Sweet Sixteen game with an iconic (in East Tennessee) finish.

Tennessee’s run would end at the hands of a 5-seed Michigan State that had their own pair of favorable coin-flips to get that far, but State at least had the pedigree and had been in the national title game the previous season. This was far less obvious and feels even more unexpected in hindsight.

While this wasn’t a buzzer-beater, it brings up a lot of questions. What if a guy that shot 29% for his career doesn’t shoot 4-5 from three out of nowhere? Goins had two games in his entire career where he made more than two threes; this was one of them. For the rest of Tennessee’s run through March, he shot 1-6 from deep. I’m sure San Diego State desperately wished he could’ve done that against them, because if he had, many things and people have very different narratives: Tennessee, San Diego State, Steve Fisher, Bruce Pearl, and many more. It even affects Kawhi Leonard’s own narrative. If SDSU makes the Sweet Sixteen or Elite Eight, does he find himself in Draft discussions a full year earlier?

Final Four

2018 11 seed Loyola Chicago (48.6% to make Round of 32, 1.6% to make Final Four)

THE VICTIMIZED: 6 seed Miami (lost 64-62).

In the lead-up to the 2018 NCAA Tournament, Loyola Chicago was everyone’s Cinderella du jour. Really! Even before they became a household name, you can read a lot of articles from people suggesting them as an excellent candidate to pull off an upset. Here’s one from Steven Ruiz, now at the Ringer. Here’s Ricky O’Donnell saying the same thing. Rodger Sherman, the Washington Post, the husk of the Chicago Tribune: basically everyone really liked Loyola to win a game.

If anything, the problem was that relatively few thought they’d win two, but pretty much every smart basketball fan I knew had Loyola to advance. We all thought Miami was fluff and might get blown off the court. Didn’t happen. For much of the second half, Miami led by 2-5 points as Loyola would consistently get close but never get over the hump. A great forgotten moment of this game that’s lost to time is that, with 12 seconds left, Loyola had two chances to tie the game. Neither went in.

Loyola had to foul, which sent future NBAer Lonnie Walker to the free throw line.

COIN FLIP #1: A career 80% free throw shooter attempts the front end of a 1-and-1.

Lonnie Walker has gone on to a fairly nice career in the NBA. As a former first-round pick and high-end recruit, he perhaps hasn’t fully lived up to expectations, but life’s outcomes can be far worse than seven seasons in the NBA and having a key bench role for the 2022-23 Lakers, a Western Conference Finals participant. (I’m using ‘participant’ very loosely. They were indeed briefly involved in the series.) In the NBA, of course, you do not have to attempt the front end of a 1-and-1. Those don’t exist.

In college, they do. Lonnie Walker lets his one and only free throw attempt fly, and the basketball hangs on the rim for seven full seasons.

COIN FLIP #2: A career 38% deep shooter is given the ball 25+ feet from the basket.

Donte Ingram has lived an interesting life: high school teammates with Jabari Parker, a professional career that has taken him everywhere from the G-League to the UAE, and only ended up at Loyola Chicago because his older brother had played there. With respect to any family events that may have happened or will happen, I’ll wager this exact frame in history is the most interesting and important Donte Ingram will ever be to the average human being.

Ingram’s first two seasons weren’t much of use from deep; he shot 31.9%. His junior year, he exploded to hit 51 of his 113 deep ball attempts…but we see outliers like that fairly often. This 2017-18 season, he’ll wrap up at a very respectable 39.2%. But as the ball is in his hands, he’s conservatively 26 or 27 feet from the basket. This isn’t an easy shot, and it’s not even a coin flip. Coins should come up heads or tails 1 out of 2 tries, not roughly 1 out of 3. But sometimes, everything comes up Milhouse.

THE AFTERMATH: In March 2018 I had an office job I’d taken two months prior and was, uh, ‘quietly’ watching the Tournament unfold because I hadn’t built up enough PTO yet. When moments like this happen, you involuntarily make some sort of noise. There is a video of me somewhere, hopefully locked away for life, learning of the ending to the 2015 Michigan/Michigan State football game at a friend’s wedding as the best man’s speech is unfolding. I am directly behind said best man in the video.

When Ingram’s shot went in, part of my office chair snapped. My boss walked over to ask if everything was all good; I said “yep, just dropped something.” Steve could’ve been watching the game himself, who knows, but decorum and such.

Anyway: think of the world where that shot doesn’t go in. You absolutely don’t know the name Sister Jean, or at least never think much of it. Porter Moser isn’t the head coach at Oklahoma. Tennessee, against a Miami team they matched up far better with, likely makes the Sweet Sixteen…to face a 7-seed Nevada team, coached by one Eric Musselman.

What if Musselman defeats Barnes before even getting to the SEC? What if Tennessee ends up in their first-ever Final Four? What if Miami was the one robbed of a deep run? There are so, so many what-ifs surrounding the ending of this game for me. We’ll never know the answer to any of them.

2023 9 seed Florida Atlantic (48.6% to make Round of 32, 3.8% to make Final Four)

THE VICTIMIZED: 8 seed Memphis (lost 66-65).

The career arc of one Penny Hardaway is a fascinating one. It’s littered with many, many what-ifs. For one, there’s Penny the player. What if he’d stayed healthy? What if Nick Anderson makes ONE (1) free throw? What if Shaq never leaves?

Penny the coach has nearly as many what-ifs. What if James Wiseman is never declared ineligible for issues that probably wouldn’t get you suspended for more than a game or two now? What if Penny never takes Emoni Bates? What if they figured out how to run a decent offense before 2024? What if he had stepped down any of the times he could’ve done so? Or if Memphis, with a new athletic director, had gotten itself out of the Penny Circus last year prior to a five-loss season?

All of those are intriguing in their own right. All of them pale in comparison to the Memphis What-If of the last 16 seasons.

THE COIN FLIP: The interpretation of a signal varies between two minds.

As inevitable as FAU seemed in hindsight, Memphis was the most popular pick in America, at least as it concerned actual value versus the public’s value. 72% of ESPN users for the 2023 Tournament picked Memphis to win this game versus an expected value of 51% to win, which was the single largest Round of 64 difference that year among teams seeded 6-8. Memphis was a known brand; FAU was not.

This game also had some extreme added importance to it occur 30 minutes before tip. Perhaps you’ve heard of it.

As the follow-up was between KenPom #23 (FAU) and #20 (Memphis), the game itself was not only close the entire way through, it also had the note that either winner would be essentially one Quadrant 4 win away from their first Sweet Sixteen since 2009 (Memphis) or ever (FAU). The entirety of the final ten minutes were played within four points either way, but on this night, it was the nation’s preferred option in Memphis that led for over half the game.

The final four minutes of this game deserve their own story; the entirety of it was played within two points in either direction. But we’re all here for one thing. With 19 seconds left, Johnell Davis drives to the basket, misses a layup through contact…and FAU fouls.

Again, context gets forgotten over time. FAU only had committed five fouls in the second half to that point. This was their sixth. Memphis inbounds the ball, and:

Chaos ensues. After turning the ball over, FAU does not get a shot up; a well-timed strip by Kendric Davis takes it out of their hands. Memphis briefly controls the ball on the ground, enough for this internationally-recognized symbol to be made.

The timeout call is seen by the official pictured, Evon Burroughs. Mr. Burroughs leads a fascinating life: a 20-year member of the Boston Police Department and an official for East Coast leagues. He’s reffed some NCAA Tournament games before; none were as close as this. Burroughs moves closer to the pile to see if Memphis does actually have possession of the ball to grant the timeout. Before he can, official Bert Smith moves in to offer his decision.

Smith’s own life is pretty private. He’ll become unwillingly famous in 2025, less as the jump-ball granter and more as the guy who kicked Grant McCasland from the Texas Tech/Houston game. Here, he sees that neither team has full possession of the ball and grants a jump ball. The problem: Memphis did actually have possession when Alex Lomax is calling for a timeout.

Smith and Burroughs briefly discuss the action; Smith overrules Burroughs. Jump-ball granted. Seconds later, FAU wins the game on a driving layup.

THE AFTERMATH: This is certainly recent enough for you to remember. Not only does FAU win the game, they defeat a 16-seed in the Round of 32, beat 4-seed Tennessee in the Sweet Sixteen, and complete one final (and very mild) upset of 3-seed Kansas State. They eventually end up a coin flip of their own away from the DADGUMMED NATIONAL TITLE GAME. Florida Atlantic.

Yet with one granted timeout and a made free throw or two, this could’ve been Memphis. The Tigers almost certainly would’ve defeated Fairleigh Dickinson in the next round to make their first Sweet Sixteen in 14 years. Even if it ended at the hands of rival Tennessee there, it still would’ve been a highly successful season and a proof of concept for Penny Hardaway going forward. He would’ve doubled his previous high number of Tournament wins in one go.

And, again, Memphis was rated even better than FAU prior to the Tournament. If they beat Tennessee, what’s stopping them from beating Kansas State? Or San Diego State? We were potentially a timeout away from National Title Game Participant Memphis. We’ll never know.

This is painful; I still don’t think it will touch this one.

The title game (!)

2011 8 seed Butler (51.7% to make Round of 32, 0.6% to make national title game)

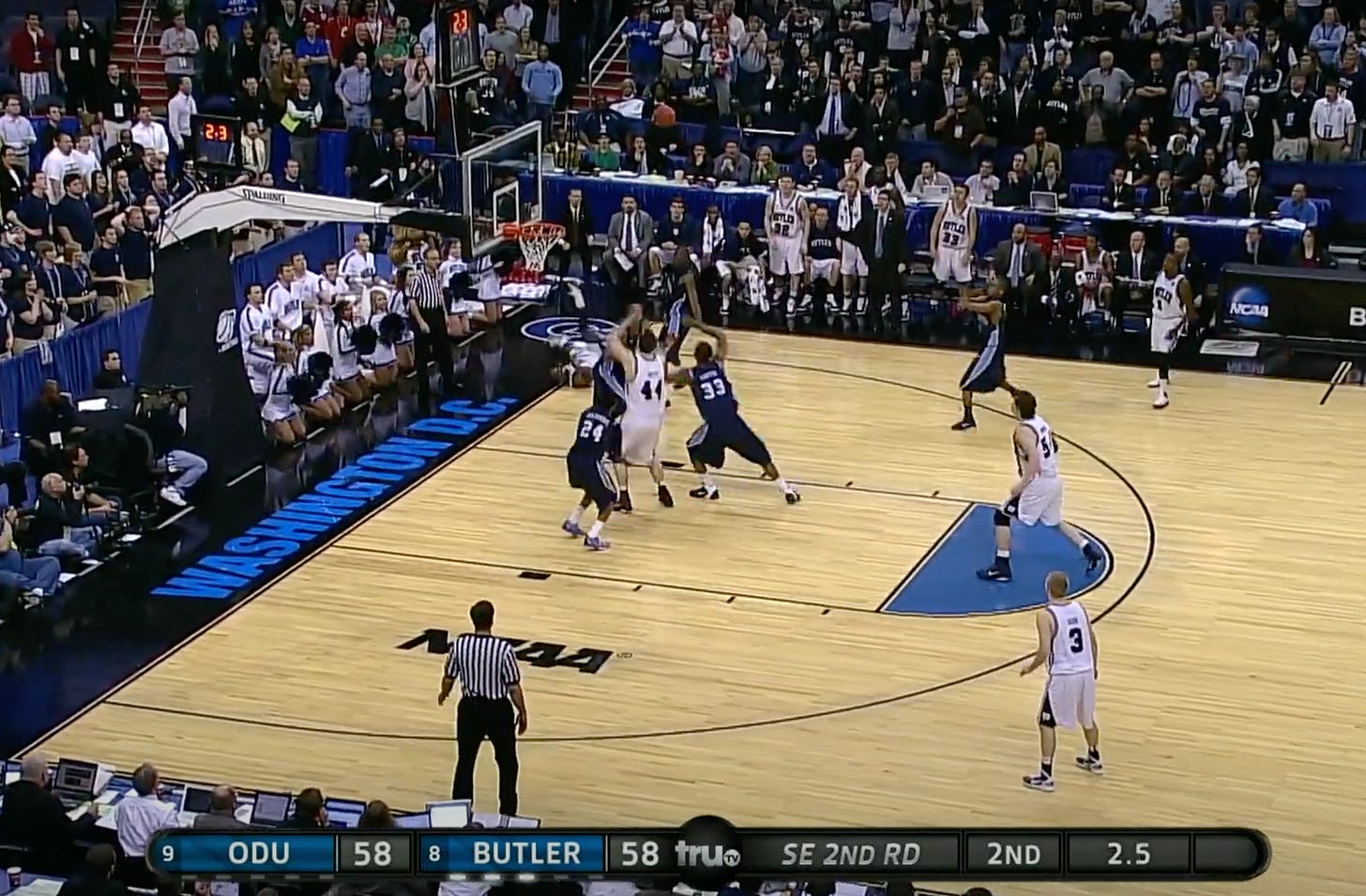

THE VICTIMIZED: 9 seed Old Dominion (lost 60-58).

No one remembers this one. Not a soul. Maybe people who are really, really invested in college basketball, but beyond that, nobody.

History is written by the winners, not the near-winners. 2010 Butler was a far better team than 2011 Butler, with far better defense, far better talent, and honestly, far better March performances. They demolished their 12-seed opposition in the first round. 13-seed Murray State gave them a 40-minute battle in the Round of 32, but aside from that, Butler’s only serious challenges en route to the title game came at the hands of 1-seed Syracuse and a Michigan State program that had made the title game the previous season.

2011 Butler was completely, totally different. In six NCAA Tournament games, their total scoring margin - TOTAL - was +9. (2010’s was +25.) They did not play a single game where they led by more than five points entering the final minute. Yet these hyper-thin margins gave them the true best Cinderella story of my lifetime, the unbelievable, unthinkable follow-up to what we all thought was the best Cinderella story of our lifetimes.

It nearly ended before it even began.

COIN FLIP #1: Two free throws.

The first 30 minutes of this game were a masterclass in Tournament Tension. The win probability chart looks like this.

Entering the final 10 minutes of the game, Butler leads 49-46. ODU trades baskets with them to get it to 51-50. Then a funny thing happens: ODU goes completely cold. Butler pushes their lead to 58-52 with 2:43 to play, holding a 91% chance of winning this game, per KenPom. Butler themselves go cold, and it’s 58-56 with a minute to go. ODU misses their first attempt, but in the ensuing scramble for the rebound, the ball flies off of Butler to stay with ODU.

Old Dominion is led by Frank Hassell, but Frank Hassell will not be who gets the ball here. The ball is given to Kent Bazemore, a junior who will go on to a 10+ year NBA career and a lot of money. But at this time in history, he’s arguably ODU’s third option sometimes offensively. He receives the inbound, and ODU clears the floor for him to go to work. He is fouled.

Now, it’s ancient history given that Bazemore ended up being a fine shooter in the NBA, but in college, he’ll wrap his career in 2012 with a free throw percentage of 58.1%. Fouling here by Butler is arguably a statistically understandable move. In fact, just six minutes prior, Bazemore was fouled on a shot attempt…and missed both free throws. Here, he steadies himself at the line:

And makes the first. He’ll re-steady and make the second. Even being charitable and using his listed FT% for 2010-11, this had about a 43% chance of happening, him hitting both free throws. One coin flip down.

COIN FLIP #2: A disastrous final possession with one perfect bounce.

Butler has the ball with 31 seconds left and the shot clock off, which Brad Stevens and crew proceed to drain down to about nine seconds before running their end-game action. It’s awful.

The ball ends up in Shawn Vanzant’s hands. Vanzant was a useful bench guy on the 2010 team and has been a solid starter in 2011, but he’s regularly the fourth option on the court for Butler. The ball usually goes to the hands of Shelvin Mack or big man Matt Howard, the two best and most skilled offensive pieces. Vanzant slips and falls, and for an eternity, the ball hangs in the air.

The first touch is by Andrew Smith, a sophomore starter that slaps the ball off the backboard. I assume he’d prefer a rebound, but hey, keep the play alive and such. The figure you see at the top of the key is Howard. Howard’s known for a lot of things - useful play, being a key member of the 2010 title game team, and having weird socks. Today, he is known for being in the right place at the right time.

THE AFTERMATH: Well, it’s obvious: what if that shot isn’t perfectly deflected off the backboard to Matt Howard? What if it’s a standard missed shot? Or it deflects out of Howard’s hands and the clock hits 0:00? What if Vanzant stumbles out of bounds and gives Old Dominion one last possession of their own?

Let’s say Old Dominion gets to overtime at 58 all and runs back the first five minutes of the game, winning overtime 10-8. ODU advances to the Round of 32 after a 68-66 defeat of 2010’s runner-up. In 94% of simulations, they draw Pittsburgh, who they have a 22.8% chance of defeating. Now, Butler’s was only 23.3%. Not a huge difference!

In the 2010-11 season, Butler went 1-3 against top-50 competition prior to the NCAA Tournament. Old Dominion actually went 4-3, defeating Clemson and Xavier on a neutral floor early in the season. For the whole ‘pedigree’ thing we use in March, which does not matter, we probably would’ve liked ODU’s chances a little more in a vacuum than Butler’s had we not known about 2010. We were banking entirely on nostalgia there, as these were functionally equal teams.

Not only that, Butler was arguably unlucky in who they drew in 2011. Their path of 9-1-4-2 was the hardest possible by seeding. This was despite drawing two of the strongest 12 and 13 seeds in Tournament history in their bracket with Utah State and Belmont, two teams in the top 25 of KenPom at the beginning of the Tournament. 2 seed Florida, at 18th, was the fifth-highest rated team in their own region.

If Old Dominion had survived Butler and then done the same thing Butler did against Pittsburgh, they still had the highest odds of eventually drawing 4-seed Wisconsin, but not by much. The odds were nearly the same to draw 12-seed Utah State in what would’ve been the first and only 9 vs. 12 matchup in Tournament history. Old Dominion would’ve been 3.5-point underdogs in that game, but in about four out of ten simulations, they win their Sweet Sixteen game.

The Elite Eight’s most likely opponent would not have been Florida; it would instead have been 3-seed BYU, who rated higher on KenPom and arguably had a better case for the 2 seed to begin with. With the flip of one coin and everything else going to plan, we were this close to either 9-seed Old Dominion or 12-seed Utah State being forty minutes from the Final Four.

And then? Well, we know the story of VCU being arguably the most shocking Final Four entry in history, but imagine the world in which Florida State beats them in the Sweet Sixteen and then plays Kansas for the Final Four bid. Do you get Old Dominion versus Kansas for Monday night? Utah State versus Kansas? Old Dominion versus Florida State, a true 1-of-1 9 vs. 10 matchup? As weird as it was, it somehow could’ve been weirder. We’ll never know, thanks to one remarkably timely tip-in.

Wild to me that 3 out of the 5 here somehow involve Tennessee either directly in the game (2010) or later on in the run of the winner of the coin flip game you highlight (2018 Loyola-Chicago and 2023 FAU). Vols have had some very strange luck with the NCAAT!

It predates your database, but the one that sticks with me is 12-seed Butler nearly knocking off 5-seed Florida in the first round in 2000.

First, Florida tied the game with 15 seconds left when 61% free throw shooter Udonis Haslem hit two from the line.

Then, despite leading by 3 with 20 seconds left in OT, they lost on a buzzer beater by Mike Miller after missing the front end of a 1-and-1.

Of course, Florida then went on a run all the way to the championship game.

Now I don’t think Butler had a ~50% chance to win the game pre-game — they were apparently 8.5 point underdogs. But if Butler had done it (ha) instead of Florida, they would still hold the record as the highest-ever seed to make the Final Four.